Introduction on Assessment of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Doppler Echocardiography

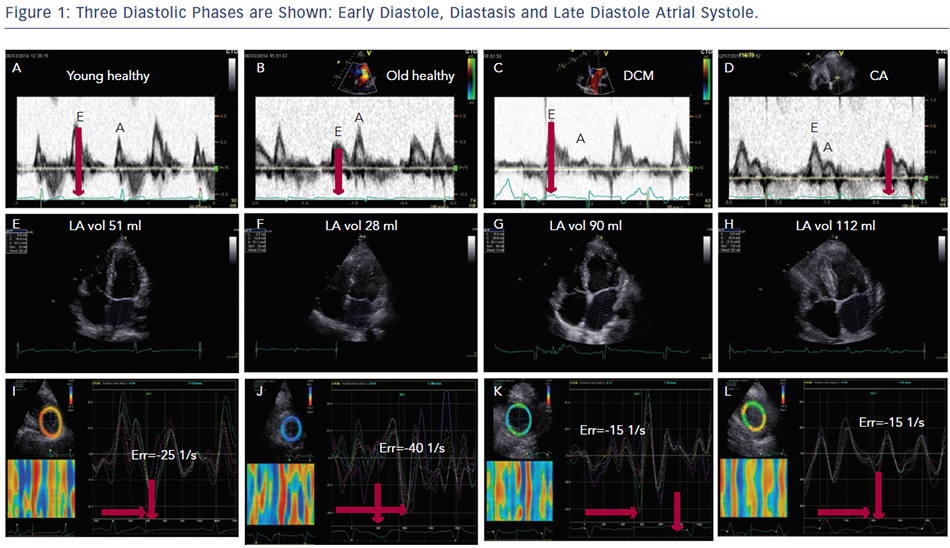

Diastole is an important period in the cardiac cycle when all heart components integrate together to secure optimum ventricular filling which determin es the stroke volume pumped by the ventricle in the succeeding cycle. Three diastolic phases are well-recognised; early diastole, diastasis and late diastole ‘atrial systole’ (Figure 1). To describe the actual events happening in the ventricle the three phases are named; early filling, diastasis and late filling.

es the stroke volume pumped by the ventricle in the succeeding cycle. Three diastolic phases are well-recognised; early diastole, diastasis and late diastole ‘atrial systole’ (Figure 1). To describe the actual events happening in the ventricle the three phases are named; early filling, diastasis and late filling.

Such description also reflects events happening between the time of mitral valve opening and closure. However, studies have already shown that patterns of diastolic events are determined by the duration and the extent of left ventricular shape change happening during the isovolumic relaxation time, with abnormal prolongation reflecting slow ventricular relaxation and abnormal shortening identifying raised left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic pressure and consequently left atrial pressure.1,2

Similar extreme patterns are often seen in patients with heart failure, but not exclusively so. While heart failure is a clinical diagnosis, it reflects various severities of cardiac function disturbances; hence there is no single diastolic pattern that is characteristic for a clinical diagnosis of heart failure. Other factors have been shown to influence diastolic function and these should be clearly understood before heart failure is discussed.

Age and Diastolic Function

With age, significant changes occur in diastolic function over and above those affecting systolic function. In the young up to the fourth decade of life, the left ventricle fills with a dominant early diastolic volume followed by a smaller late diastolic volume. The pronounced early diastolic phase is caused by the low (negative) apical pressures compared with those at the base of the LV, maintained by an apical untwist, anticlockwise rotation of the cardiac apex, (Figure 1A–C) which results in a suction effect. With progressive collagen deposition in the myocardium, in the fifth decade of life, its relaxation slows and is delayed. This results in prolongation of isovolumic relaxation time due to delayed opening of the mitral valve. This occurs in the overall diastolic period but especially in the early diastolic phase, (Figure 1B) and results in compromised early filling component (or volume) with a compensatory increase in the late diastolic component and a more pronounced apical untwist (Figure 1J).3 These changes are greater if there is additional pathology affecting the left ventricle e.g. coronary artery disease or systemic hypertension. In the worst cases, the early filling can be completely truncated and the left ventricle fills with an isolated late diastolic filling component. If such patients develop atrial fibrillation, the isolated late diastolic filling component will be shifted to early diastole but at the expense of raising the left atrial pressure and reducing the stroke volume.4,5

Electric Function and Diastole

Diastolic phases are also influenced by the electrical pattern of activation (depolarisation) and repolarisation. QRS broadening, irrespective of bundle branch block (BBB) is associated with delayed activation and delayed inward motion. This is reflected in delayed segmental outward motion with post-ejection shortening, the combination of the two results in delayed onset and shortened early diastolic filling of the left ventricle.6 The same pattern is seen in coronary artery disease, particularly in patients with Q wave infarction.7 Left ventricular filling pattern could also be affected by other electric abnormalities. An absent P wave (e.g. through atrial fibrillation) results in absent late diastolic filling component, which compromises the overall filling and stroke volume of the ventricle.8,9

The most sensitive myocardial layer to coronary artery disease and ischaemia is the subendocardium, even in patients with no obstructive lesions in the epicardial vessels. Indeed, early subendocardial dysfunction has been shown to be predominantly diastolic and as it worsens it becomes systolic. Disturbances are similar to those described above but the delayed segmental shortening and lengthening is more profound.10 These disturbances will affect the LV filling pattern as previously described.11

In patients with scarred myocardium from a prior infarction, the overall function of that segment might be dyssynchronous, hence adding to the extent of filling abnormalities. In severe cases and with more than one dyssynchronous segment the left ventricle might fill with an isolated late diastolic component.10,12