No Stump, Ostial Occlusion or Occlusion at Take-off

Without a doubt recanalisation is much easier if a stump can be identified, and tapered stumps are more favourable than blunt stumps, which are more likely to be experienced in very old occlusions. If no stump can be identied, some operators primarily prefer a retrograde approach via collaterals although antegrade wiring may still be successful in >50 % of cases. This is why I do start antegrade in almost all 'no stump-cases. Several techniques were developed to help identify the correct antegrade entry. If a side branch is available at the suspected takeoff, IVUS may be used to guide the wire entry. Less expensive strategies are the Sesame-open technique that requires a wire left in the side branch at take-off. The wire not only may serve as a marker for the take-off but also sometimes lever the side branch and enlarge the bifurcation angle and thus demask a tiny stump. A more aggressive approach is the side branch technique, an attempt to break the proximal cap with a balloon inflated in the main vessel and side branch across the take-off. This technique may successfully open the entry in 30-40 % of cases with a risk of subintimal dissection requiring re-entry with a tapered stiff wire.

If I do not succeed antegradely within 5-10 minutes of fluoroscopy time or a dissection occurs with the risk of extending distally I do stop the antegrade approach and search my cine runs for optimal collaterals to continue retrograde.

Heavy Calcification

About 60 % of chronic occlusions involve calcification that can be detected during angiography. The EuroCTO registry ERCTO grades calcification as:

1. absent;

2. mild (spots of calcium);

3. moderate (<50 % of vessel circumference involved); and

4. severe (>50 % of vessel circumference calcified) - severe

calcification was an independent predictor of lower success rate.

Although some operators prefer to start antegrade with a soft tapered polymer wire (e.g. Fielder XT) to probe invisible microchannels, in my experience this is a waste of time in 90 % of cases since in most cases it is only possible to break up the rocky proximal cap with a tapered stiff wire like Confianza 9 or 12. I do recognise that in 10 % of cases even severe calcification may mainly be located outside the former vessel lumen and what initially appeared like a rock-hard barrier is quite easy to cross with a moderately stiff wire. After having entered the CTO I continue with the same wire if the course is straight and switch to a softer steerable wire (e.g. Ultimate 3g or Pilot 150) if the course is tortuous. The distal cap is always softer than the proximal but often still requires to be punctured preferably at its centre. If the distal vessel cannot be re-entered correctly one should avoid extensive manipulations that can easily shear off collaterals and prohibit visualisation of the distal vessel. Instead of losing distal patency and time the operator should leave the antegrade wire in place and switch to retrograde wire crossing or reversed controlled antegrade and retrograde subintimal tracking (CART). In general it is easier to enter a calcified CTO from retrograde than antegrade because the distal cap is always softer.

Balloon Failure

After successful antegrade wire crossing it may be impossible to follow with a small  balloon even after having increased the guiding support with an anchoring wire or balloon in a proximal side branch.

balloon even after having increased the guiding support with an anchoring wire or balloon in a proximal side branch.

Rotablator may be successful but it is not wise to pull the wire and a change for a rotawire unless all other options failed. The options that will be successful in >70 % are Tornus, twisted in counter-clockwise, or Corsair, twisted in clockwise and counter-clockwise, although the latter is more fragile and operators should avoid extensive rotations on the same spot indicating that the device might be captured and break.

In about 10 % of the balloon failures Tornus and Corsair will fail as well. In these cases Laser is the best option; however, it is available only in a few institutions. Then it is worth trying to increase the lumen of the channel by paralleling a second stiff wire, but staying strictly parallel along the whole occlusion is not easy either. Before giving up we try to advance a micocatheter as close as possible and then exchange the CTO wire for a rotablator wire and then rotablator with a 1.25 burr.

Tortuous Coronary Artery

Tortuosity in the ERCTO registry is defined as none (straight: no bend >70° , slight: one bend >70° , moderate: two bends >70° or one bend >90° , severe: two bends >90° or one bend >120°).

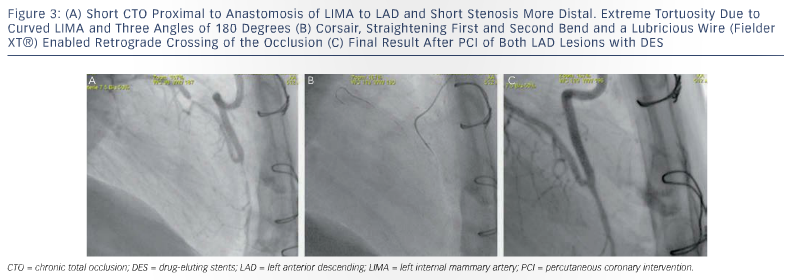

The best strategy to overcome tortuosity is to use a Corsair, which thanks to its flexibility, kink resistance and lubricious surface render optimal steerability even to non-polymer wires. Polymer wires should be selected in very tortuous anatomy as depicted in Figure 3 (A-C). Sometimes progress can only be achieved by keeping more than one wire in place to straighten the vessel.

Dissection

Almost all recanalisations to some extent involve a wire exit and re-entry, and thus limited dissection with subintimal stenting. This limited mistreatment of the coronary appears not to unfavourably influence short and long-term results. However, intentional extended subintimal tracking, what I view as Ramboplasty and stenting as practised with STAR-like techniques, not only may amputate side branches but also bear the risk of unacceptable reocclusion rates of more than 50 %.27 Therefore if a subintimal wire cannot be steered back to the lumen after 10-15 mm, one should consider either switching to retrograde or to a more sophisticated re-entry technique like IVUS-guided re-entry or the BridgePoint Stingray system.28