Major bleeding or haemorrhage following a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is not a benign event. There is now co nvincing evidence that it independently predicts increased mortality and adverse outcomes in patients.1,2 The adverse outcomes associated with a bleeding event are not just as a direct result of the haemorrhagic event, such as whether or not a patient survives their gastrointestinal (GI) or intracranial haemorrhage, but are seen in the subsequent progress of the patient up to at least one year after the event. Herein, we discuss the recent data on post-PCI bleeding and the difficulties in comparing different studies with different methodologies and definitions of major haemorrhage. We then consider the mechanisms through which bleeding complications may affect longer-term outcomes and discuss bleeding avoidance strategies to minimise such bleeding events.

nvincing evidence that it independently predicts increased mortality and adverse outcomes in patients.1,2 The adverse outcomes associated with a bleeding event are not just as a direct result of the haemorrhagic event, such as whether or not a patient survives their gastrointestinal (GI) or intracranial haemorrhage, but are seen in the subsequent progress of the patient up to at least one year after the event. Herein, we discuss the recent data on post-PCI bleeding and the difficulties in comparing different studies with different methodologies and definitions of major haemorrhage. We then consider the mechanisms through which bleeding complications may affect longer-term outcomes and discuss bleeding avoidance strategies to minimise such bleeding events.

Importance of Definition

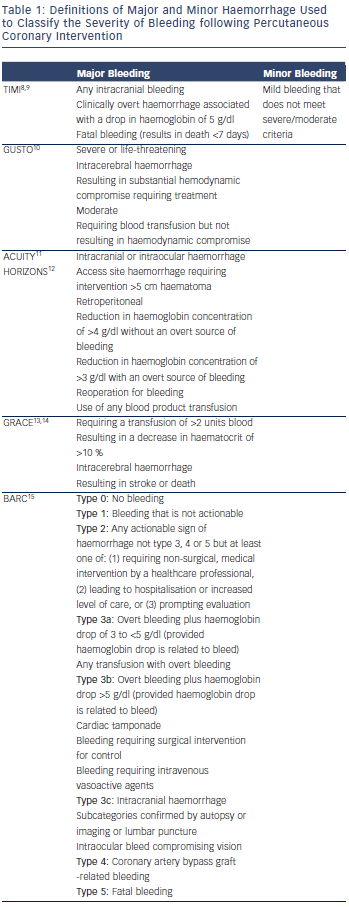

Major bleeding rates in modern PCI practice are highly variable in the published literature. They range from less than 1 % to nearly 10 % in PCI for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). This is dependent on a number of procedural factors but also importantly on the definition of major haemorrhage the study uses.3–7 Definitions are based on a combination of laboratory and clinical factors to indicate severity (see Table 1).8–15 The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) bleeding criteria have been used for over 25 years. They were developed to classify major and minor haemorrhage following thrombolysis of STEMI and relied predominantly on laboratory measures, such as haemoglobin. Over time the TIMI definition has evolved to encompass more bleeding complications to reflect modern practice and require clinical, or radiographic, evidence of actual blood loss.8,9 However, the TIMI definition is still biased to identify acute and very severe bleeds and there can be uncertainty about when peak and trough haemoglobin level should be measured. Other criticisms include the nomenclature. A TIMI ‘minor’ bleed can have a haemoglobin drop of 3–5g/l, which is not minor and indeed could have life-threatening consequences. Recent consensus statements by the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) have tried to standardise bleeding definitions, but the success of this endeavour will only be judged in time.15

The definition of peri-procedural major bleed used can eliminate the effect of a given therapeutic intervention and thereby influence the outcome of a study. The RIVAL trial,16 a landmark, multicentre trial comparing radial and femoral PCI, did not demonstrate a significant difference in non-coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) related major bleeding, as defined by the study. RIVAL defined major bleeding as either: fatal, requiring transfusion of 2 or more units, causing hypotension requiring inotropes, requiring surgery, leading to disability, intracranial bleeding or a drop of >50 g/l of haemoglobin. However, using a broader definition of major bleeding, such as the ACUITY definition,11 which includes bleeds causing large haemotomas or pseudoaneurysms requiring intervention, then radial access was associated with a significant reduction in major bleeding (odds ratio [OR] 0.43; p<0.00001) and thus the overall impact of the trial is different. It is therefore important to consider the definition of haemorrhage used in any trial related to PCI outcomes, particularly if comparison is being made between trials with different methodology. This may have a profound influence on a day-to-day practice for the clinical cardiologist and, indeed, may help influence a decision to switch from femoral to radial practice or use glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPIs), based on the ‘headline’ message of a trial.