Natriuretic Peptide Guided Heart Failure Therapy

Levels of natriuretic peptides, other than BNP and the N-terminal residual of its pro-hormone NT-proBNP, have little or no clinical role in HF, at least in Europe and the US. Other biomarkers have not yet been sufficiently studied in guiding chronic therapy. Therefore, this review focuses largely on these two peptides. In order to understand  the concept of natriuretic peptide-guided therapy in chronic HF several aspects are important, as summarised in a recent review.9 Thus, HF is a very costly chronic disease (around 2 % of the total healthcare budget spent for HF) with increasing prevalence (at present there about 10 million HF patients in Europe).10 Prognosis remains poor despite significant advances in therapy11,12 and to some extent, this is related to the insufficient use of available treatment in HF.13,14 Achieving optimal therapy seems to be extremely difficult and additional markers to identify those patients in most need may be helpful. Natriuretic peptides may be very useful in this as they are strong prognostic markers across the whole spectrum of HF, particularly in the chronic stage15 and seem to change relatively little if patients are clinically stable.16 More importantly, natriuretic peptides change over time in parallel with change in prognosis17,18 and treatment of chronic HF influences plasma levels of natriuretic peptides. Thus, loop diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitors, angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARB) and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), as well as cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT), may cause a fall in natriuretic peptide levels. The response to beta-blockade is more complex with a potential initial rise, but long-term fall.9 Taken together, natriuretic peptides may be very suitable for monitoring and guiding chronic therapy in HF.

the concept of natriuretic peptide-guided therapy in chronic HF several aspects are important, as summarised in a recent review.9 Thus, HF is a very costly chronic disease (around 2 % of the total healthcare budget spent for HF) with increasing prevalence (at present there about 10 million HF patients in Europe).10 Prognosis remains poor despite significant advances in therapy11,12 and to some extent, this is related to the insufficient use of available treatment in HF.13,14 Achieving optimal therapy seems to be extremely difficult and additional markers to identify those patients in most need may be helpful. Natriuretic peptides may be very useful in this as they are strong prognostic markers across the whole spectrum of HF, particularly in the chronic stage15 and seem to change relatively little if patients are clinically stable.16 More importantly, natriuretic peptides change over time in parallel with change in prognosis17,18 and treatment of chronic HF influences plasma levels of natriuretic peptides. Thus, loop diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitors, angiotensin-II receptor blockers (ARB) and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRA), as well as cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT), may cause a fall in natriuretic peptide levels. The response to beta-blockade is more complex with a potential initial rise, but long-term fall.9 Taken together, natriuretic peptides may be very suitable for monitoring and guiding chronic therapy in HF.

Clinical Trials

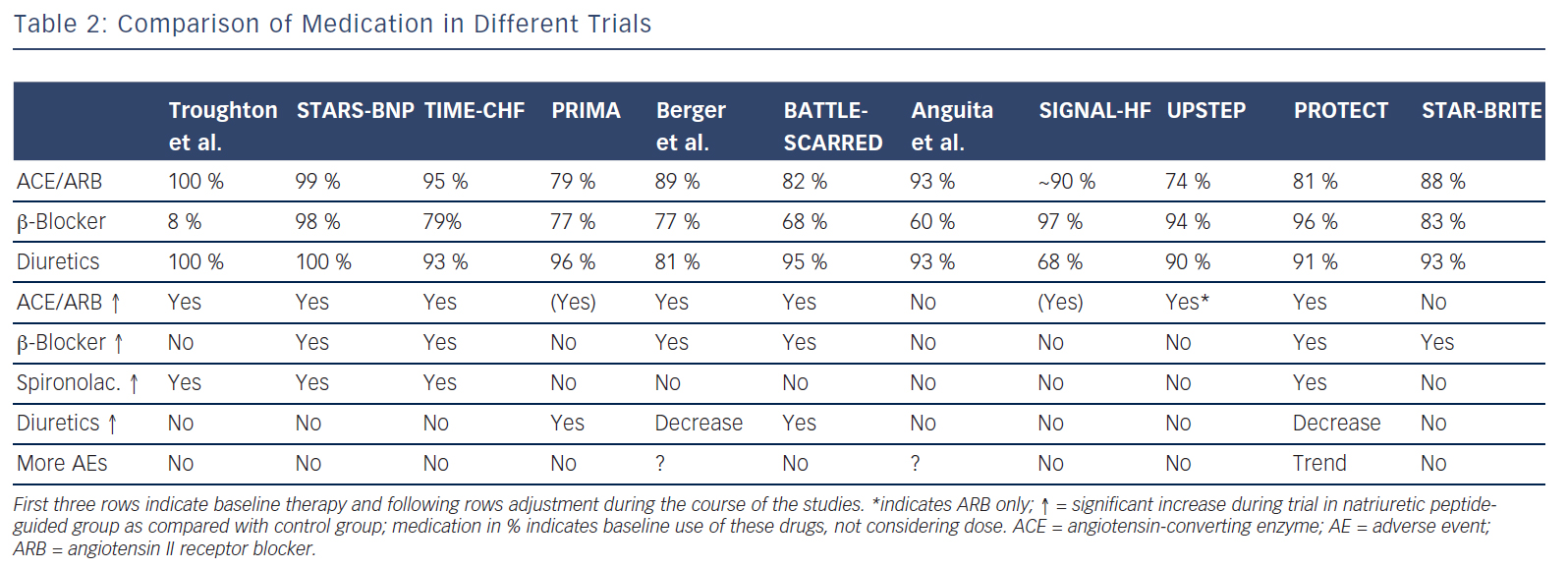

Several trials have investigated the concept that natriuretic peptide may help to optimise and up-titrate medical therapy in chronic HF (Tables 1 and 2).1,19–30 These  studies included between 60 and 499 patients. The largest study additionally included 123 patients with preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF),20,27,31 whereas in some of the other studies a smaller proportion of patients with preserved LVEF (HFpEF) were included in the main study without distinction based on LVEF (Table 1). In addition, a very small study of 41 patients investigated BNPguidance to up-titrate beta-blockade.32 A medium-sized single-blinded trial (n=407) investigated the value of increasing levels of NT-proBNP as an indicator for deterioration in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) already on optimised medical therapy.33 This latter study found no effect, but the intervention did not result in any changes in therapy. This suggests that measuring natriuretic peptide levels might be more helpful for up-titrating and optimising therapy in HF. More than one trial investigating natriuretic peptides use in monitoring HF patients already on optimal therapy is required before a clear answer can be given as to whether long-term monitoring using natriuretic peptides is of value. Effects of NT-proBNP guidance during 12 months’ optimising phase were maintained long-term even if NT-proBNP levels were no longer used to monitor patients in TIME-CHF28.

studies included between 60 and 499 patients. The largest study additionally included 123 patients with preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF),20,27,31 whereas in some of the other studies a smaller proportion of patients with preserved LVEF (HFpEF) were included in the main study without distinction based on LVEF (Table 1). In addition, a very small study of 41 patients investigated BNPguidance to up-titrate beta-blockade.32 A medium-sized single-blinded trial (n=407) investigated the value of increasing levels of NT-proBNP as an indicator for deterioration in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) already on optimised medical therapy.33 This latter study found no effect, but the intervention did not result in any changes in therapy. This suggests that measuring natriuretic peptide levels might be more helpful for up-titrating and optimising therapy in HF. More than one trial investigating natriuretic peptides use in monitoring HF patients already on optimal therapy is required before a clear answer can be given as to whether long-term monitoring using natriuretic peptides is of value. Effects of NT-proBNP guidance during 12 months’ optimising phase were maintained long-term even if NT-proBNP levels were no longer used to monitor patients in TIME-CHF28.

Because the limited number of patients included in these trials was insufficient to convincingly show beneficial effects of natriuretic peptideguided therapy, several meta-analyses were performed. Each showed positive effects on HF-related hospitalisation and mortality. Figure 1 depicts the forest plot of all-cause mortality of the 11 individual trials1,19–26,29,30 investigating optimising medication based on natriuretic peptide levels (Review Manager Version 5.3, Copenhagen, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration 2014). There was no significant heterogeneity between the trials, as was also found by all meta-analyses.

Is there any Interaction with Sub-groups?

A recent analysis based on IPD of eight of the trials1,19–24,27,30 showed different response to natriuretic peptide-guided therapy comparing HFrEF and HFpEF.34 This analysis also included the largest HFpEF population of all the studies,27 in contrast to all other meta-analyses. Whereas HFrEF patients defined as left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)≤45 % on natriuretic peptide guided therapy had a reduced mortality with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.78 (P=0.03), patients with HFpEF did not benefit at all (HR=1.22, P=0.41) with a strong interaction of the treatment response between the two groups (P<0.02).34 This difference comes as no surprise given that there is as  yet no effective treatment for HFpEF, while the medication mentioned above – apart from diuretics – clearly improved outcome in HFrEF.2 Thus, intensifying ineffective treatment based on any means may not improve outcome. It has to be noted, however, that all the natriuretic peptide-guided trials were planned and conducted when this difference was largely unknown. Moreover in clinical practice, the same medication is still often used in HFpEF as it is recommended for HFrEF patients.35

yet no effective treatment for HFpEF, while the medication mentioned above – apart from diuretics – clearly improved outcome in HFrEF.2 Thus, intensifying ineffective treatment based on any means may not improve outcome. It has to be noted, however, that all the natriuretic peptide-guided trials were planned and conducted when this difference was largely unknown. Moreover in clinical practice, the same medication is still often used in HFpEF as it is recommended for HFrEF patients.35

The results from this IPD meta-analysis argues against such practice. Results from the natriuretic peptide-guided trials may provide important information on our understanding of treatment response in HF and the pathophysiology of the disease. In addition to the difference in the treatment response in HFpEF versus HFrEF, the potential effect of age is of interest. Some of the trials and the IPD-based meta-analysis reported significant differences in the effect of natriuretic peptide-guided therapy depending on age. Whereas a clearly significant positive effect was seen in patients aged under 75 years, no effect was seen in patients aged 75 and over.7,20,23 The recent additional analysis of the IPD shows that this difference may be explained by either the presence or absence of co-morbidities.34 Thus, more intensified HF therapy based on natriuretic peptide levels is less or not effective in the presence of significant co-morbidities. Two important questions arise from this finding. First, what are the reasons for this? Second, does this apply to HF therapy in general, i.e. is up-titration of medication in HF less efficacious in the presence of significant co-morbidities? Both questions cannot be easily answered.

Briefly, co-morbidities might interfere with and change response to treatment, possibly resulting in reduced tolerance of [high doses of] medication. However, this has not yet been fully studied. Regarding natriuretic peptide-guided therapy, limited information suggests that natriuretic peptide guided-therapy and therefore more intensive treatment is safe and not accompanied by excessive side effects apart from mild hypotension36(see Table 2). This also applied to worsening renal failure and hypokalaemia, although doses of loop diuretics and spironolactone were strongly related to these events, suggesting that up-titration of medication based on natriuretic peptides is safe when sufficient control is applied.37,38 Moreover, results show that natriuretic peptide-guided therapy may improve cardiac structure and function30,39 and that this effect is similarly present in those aged 75 years or older.40

Thus, the effects on HF itself in HFrEF may be irrespective of age and co-morbidities, but may be to some extent concealed by events related to co-morbidities. This is in line with the lack of interaction with age in the large randomised controlled treatment trials in HF2, as in these trials, patients with significant co-morbidities were largely excluded. Adequate trials are required to address this important question, in particular, prospective studies are urgently needed investigating the effects of treatment following current guidelines in the frail elderly with significant co-morbidities. This not only applies to natriuretic peptideguided therapy, but even more so to treatment in general.