Clinical Benefit of Trimetazidine in Patients with Heart Failure

At present, trimetazidine is the only pharmaceutical modulator of cardiac metabolism, and is widely available in clinical practice. In addition to the approved indication (i.e. the symptomatic treatment of stable angina), there has been growing evidence that trimetazidine prevents ischaemia–reperfusion injury after myocardial revascularisation procedures and improves cardiac function in heart failure.

The beneficial effect of trimetazidine in heart failure has been attributed to shifting energy production from fatty acid oxidation to glucose oxidation, which leads to an increased production of high- energy phosphates as well as an improvement in endothelial function, reduction in calcium overload and free radical-induced injury, and inhibition of cell apoptosis and cardiac fibrosis with further beneficial effect on myocardial viability.31–35

The trimetazidine-induced beneficial effect on left ventricular function in patients with heart failure has been shown to be associated with an improvement of the cardiac phosphocreatine:ATP ratio by 33%, indicating the preservation of myocardial high-energy phosphate levels.36 Moreover, the observation that this beneficial effect is also paralleled by a reduction in the whole-body rate of energy expenditure indicates that this effect may be mediated through decreased metabolic demand in peripheral tissues.37 It was found that trimetazidine improves the functional capacity in patients with heart failure when used in conjunction with exercise.38 This positive effect on functional capacity could be explained by the cytoprotective mechanism exerted by trimetazidine on skeletal muscle integrity.39 It is important that trimetazidine acts without affecting heart rate and blood pressure.

Numerous clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of trimetazidine in improving New York Heart Association (NYHA) heart failure class, exercise tolerance, quality of life, LVEF, cardiac volumes, and inflammation and endothelial function in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy.40–46 There are considerably fewer studies that have examined the efficacy of trimetazidine in patients with heart failure of non-ischaemic aetiology.47,48 Nevertheless, trimetazidine has been shown to significantly improve cardiac function and exercise tolerance in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and has extracardiac metabolic effects such as increase in high-density lipoprotein levels and reduction of blood insulin and C-reactive protein levels.

Interestingly, trimetazidine has potential electrophysiological properties. Several studies have demonstrated the beneficial effects of trimetazidine on the parameters of heart rate variability, P-wave duration and dispersion and changes in QT interval that are considered markers of the increased risk of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in patients with heart failure.49–52

In recent years, the ability of trimetazidine to reduce the rate of all- cause mortality in patients with heart failure has become a subject of particular interest. This intriguing observation was made in a number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and retrospective cohort studies.

The ability of trimetazidine to improve survival rates in patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy and multivessel coronary artery disease was first evidenced by El-Kady et al. in a single-centre, open-label, randomised trial.53 In this study, 200 patients were randomised to receive trimetazidine or placebo for 24 months. After 2 years of treatment survival rates were 92 % for the patients treated with trimetazidine versus 62 % for the patients in the placebo group.

In another open-label study, Fragasso et al. randomised 45 patients with heart failure to either conventional therapy plus trimetazidine or conventional therapy alone, with a mean follow-up of 13 months.45 It was noted that, apart from the patients who died during the follow- up period, patients randomised to conventional therapy alone had a higher incidence of cumulative cardiovascular events compared with the patients randomised to trimetazidine.

In the 48-month extension phase and post-hoc analysis of a single- centre, open-label, randomised Villa Pini d’Abruzzo trimetazidine study, 61 patients with heart failure  were randomised to receive trimetazidine in addition to conventional treatment or to continue their usual drug therapy for 4 years.54 This analysis showed that, in comparison with conventional therapy alone, the addition of trimetazidine significantly reduced the rate of all-cause mortality by 56 % (p=0.005) and heart failure hospitalisation by 47 % (p=0.002), and improved patients’ functional status (NYHA class and 6-min walking test) and LVEF.

were randomised to receive trimetazidine in addition to conventional treatment or to continue their usual drug therapy for 4 years.54 This analysis showed that, in comparison with conventional therapy alone, the addition of trimetazidine significantly reduced the rate of all-cause mortality by 56 % (p=0.005) and heart failure hospitalisation by 47 % (p=0.002), and improved patients’ functional status (NYHA class and 6-min walking test) and LVEF.

The positive long-term effect of trimetazidine on the reduction of mortality rates was also demonstrated in another single-centre, open-label, randomised trial.55 The results of this study showed a significant effect of trimetazidine modified release in postmyocardial infarction patients with angina and heart failure in terms of a 15 % reduction in the all-cause mortality rate over the 6-year follow-up period (p<0.05) and of major cardiovascular events such as cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, acute stroke, need for coronary revascularisation, hospitalisation for unstable angina or heart failure (by 15.7 %; p<0.05).

The results of these studies are in line with those reported by Fragasso et al. in a large, international, multi-centre retrospective cohort study involving 669 patients with heart failure (including 362 patients receiving trimetazidine).56 It was noted that the addition of trimetazidine to conventional therapy is associated with a significantly reduced all-cause (by 11.3 %; p=0.015) and cardiovascular mortality rate (by 8.5 %; p=0.050), as well as, a reduction in hospitalisations for any cardiovascular cause (by 10.4 %; p<0.001).

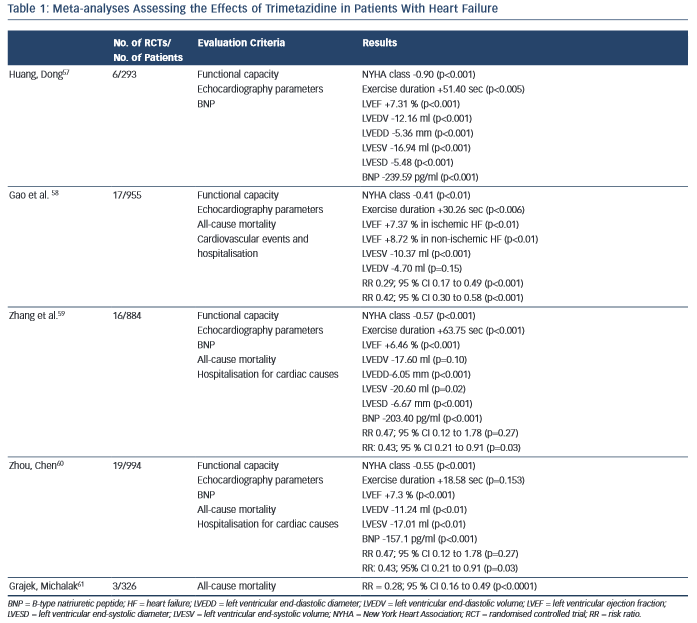

Several meta-analyses of RCTs have been performed to estimate the effects of trimetazidine treatment in patients with heart failure. Table 1 summarises the characteristics and key results of these meta-analyses.

The first meta-analysis was performed by Huang and Dong and included data for 293 patients with heart failure from four RCTs and two crossover design trials.57 Huang and Dong demonstrated that, compared with the control group, trimetazidine reduced the NYHA class and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) level, increased exercise duration, improved the indices of cardiac function and quality of life.

Later, Gao et al. published a meta-analysis that pooled data from 17 RCTs, which included 955 patients with heart failure.58 In comparison with placebo, trimetazidine treatment was associated with NYHA class reduction, increased exercise tolerance and improvement of LVEF in patients with heart failure of both ischaemic and non-ischaemic aetiology. The most interesting finding was that in patients with heart failure the use of trimetazidine reduced the rates of cardiovascular events and hospitalisations, and all-cause mortality.

In a meta-analysis performed by Zhang et al., data from 16 RCTs with 884 patients with heart failure also showed the ability of trimetazidine to decrease NYHA class, increase exercise tolerance, improve LVEF and decrease left ventricular end-systolic and end-diastolic diameters, as well as the level of BNP.59 As in the meta-analysis by Gao et al.,58 Zhang et al. noted that trimetazidine reduced the rate of hospitalisation for cardiovascular reasons in patients with heart failure, but not the all-cause mortality rate.

An updated meta-analysis by Zhou and Chen that included data for 994 patients with heart failure from 19 RCTs confirmed the reduction of NYHA class, cardiac volumes and BNP level and improvement in LVEF in patients treated with trimetazidine.60 Again, a reduction in the rate of hospitalisation for cardiac causes was observed. However, there were no significant differences in exercise duration and all- cause mortality rates between patients treated with trimetazidine and those receiving placebo.

Recently Grajek and Michalak presented a meta-analysis evaluating the effect of trimetazidine on all-cause mortality rate in patients with heart failure.61 A total of 326 patients from three RCTs were analysed: 164 who received trimetazidine in addition to a pharmacological heart failure therapy and 162 controls. The results again showed a significant reduction in all-cause mortality rate among patients with heart failure treated with trimetazidine.

The main limitation of these meta-analyses is that they were based on under-powered studies. The number of patients with heart failure included in these meta-analyses was relatively small. Other limitations include the differing designs of the included studies and wide variations in follow-up durations.

The limitations of meta-analyses and retrospective trials should not outweigh other proven facts, such as the ability of trimetazidine to relieve symptoms, improve the quality of life and increase the functional capacity of patients with heart failure. Presently, much importance is given to these parameters; the current European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure consider them as important targets in the management of patients.3 Taking into account the above-mentioned finding and also the evidence that trimetazidine delays or reverses left ventricular remodelling in patients with heart failure, we can expect that this agent will be added to the guidelines on the management of patients with heart failure. Moreover, the first steps have already been taken: today, trimetazidine is already included in a number of national guidelines as an agent for treatment of patients with heart failure of ischaemic aetiology.62–64

Trimetazidine can be recommended to patients with heart failure of ischaemic aetiology used in addition to an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor (or an angiotensin receptor blocker if ACE inhibitors are not tolerated), a -blocker and a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist to eliminate the symptoms, increase the functional capacity, normalise haemodynamic parameters and provide a possible reduction in the risk of death and re-hospitalisation.