ESC Guidelines for Patient Self-management in Chronic Heart Failure

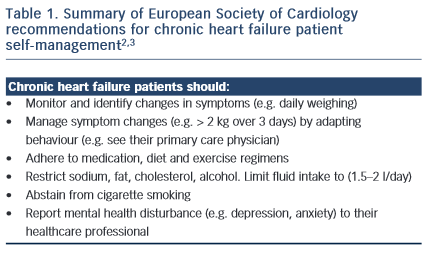

The gold-standard of patient self-management in chronic heart failure (CHF) can be defined as “daily activities that maintain clinical stability”.1 This requires that patients monitor their symptoms, adhere to their medication, diet and exercise regimens and manage symptoms by recognising changes and responding by either adapting behaviours or by seeking appropriate assistance.2 Patient self-management is linked to reduced mortality risk and fewer hospital admissions; however, there is less  certainty with regard to the benefits of some aspects of self-care, such as lifestyle choices and fluid restriction.2 According to the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure,3 self-management is integral to achieving best patient outcomes: to reduce mortality and improve quality of life.

certainty with regard to the benefits of some aspects of self-care, such as lifestyle choices and fluid restriction.2 According to the European Society of Cardiology Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure,3 self-management is integral to achieving best patient outcomes: to reduce mortality and improve quality of life.

Self-management in CHF usually involves behavioural adaptation. Patients may need to learn new behaviours, such as learning how to monitor and manage symptoms and complex medical regimens. Patients may also need to abstain (e.g. cease smoking), adapt (e.g. restrict their sodium, cholesterol and fluid intake) and maintain (e.g. exercise regularly) other behaviours. While targets have been recommended for best CHF management practice (such as to restrict fluid to 1.5 litres per day and to monitor weight changes > 2 kgs over three days), these need to be individualised according to the patient symptom and disease status profile and reset regularly. From the patient perspective, this increases the complexity of self-management and intensifies the cognitive, behavioural and motivational demands of self-care. However, for most patients the empowerment rendered by self-care results in a sense of control and achievement, rather than a feeling of passivity and helplessness. This applies to the partners of patients, as well as to the patients themselves. Within the general framework of the management strategy, the patient must experience some sense of control. For example, the patient needs to control the diuretics – the diuretics should not control the patient. Thus flexibility of dosage timing needs to fit in with the sociological constraints of the patient’s day-to-day life.

It is also important to stress that self-care can only work satisfactorily when there is partnership with – and trust in – the healthcare professional team. For example, even in the absence of cognitive impairment, a patient cannot safely alter their own diuretic doses (as a response to their weight and fluid status) unless the parameters are regularly reviewed and reset at a clinic visit. Changes in adipose tissue and muscle mass can render previous “target weights” incorrect, resulting in either heart failure decompensation on the one hand or dehydration on the other, especially for relatively unstable patients. Therefore re-setting of weight targets is very important – but takes considerable clinical skill. Evaluation of volume status includes clinical assessment of symptoms suggestive of either hyper- or hypo-volaemia; measurement of blood pressure, both recumbent and standing; evaluation of jugular venous pressure with patient propped up at 45 degrees, as well as lying flat (ensuring that the veins fill appropriately); rise or fall of serum creatinine and estimation of B-natriuretic peptide. The target weight for the patient self-management can then be reset.