Self-management Interventions in CHF: Do They Work?

Patient self-management is proposed to be a cornerstone of CHF outcomes,3 although evidence to support this is limited.4 Nonetheless, poor patient adherence is linked to hospital readmissions.5,6 Patient disability, disease burden and decompensation undermine adherence to recommended self-management behaviours.7,8 Non-adherence to recommended treatment plans is common in CHF,6,9 with reports that up to 60 % of patients do not adhere to their medication regimens as prescribed and up to 80 % do not adhere to lifestyle recommendations.5,10 Van der Waal et al6 also found that patients tend to tolerate exacerbations in their CHF symptoms and delay seeking assistance.

Health literacy has also been linked to a patient’s ability to self- manage.9 Low health literacy has been shown to be an independent predictor of mortality11 and hospitalisations.12,13 It is unknown as to whether poor health literacy is a primary cause of poor health outcomes or whether it is an underlying problem of other issues, such as low socioeconomic status, inadequate access to health services or a low trust in healthcare providers. Nevertheless, low health literacy needs to be addressed in an effort to improve knowledge and self- management skills.

A variety of strategies has been proposed to support patient self- management, such as early and targeted screening of patients to identify and resolve capacity deficits (e.g. limited literacy, cognitive and physical impairment) and psychosocial obstacles (e.g. depression and anxiety) that may undermine self-care. For example, whole system informing self-management engagement (WISE) training involves an assessment of patient needs, motivation and capacity, shared decision making and agreement on a  management plan to support patient self- care; WISE training has produced improvements in patient outcomes in several chronic disease settings,14 but is untested in CHF.

management plan to support patient self- care; WISE training has produced improvements in patient outcomes in several chronic disease settings,14 but is untested in CHF.

Both depression and anxiety are associated with poor adherence to medical regimens,15 this in turn having a marked effect on patient self-management. The management of depression in cardiac patients therefore is extremely important if patients are to become engaged in self-management.16 The importance of a relevant professional relationship, with continuity over time, cannot be over-emphasised for the maintenance of patient engagement, collaboration and appropriate self-management.

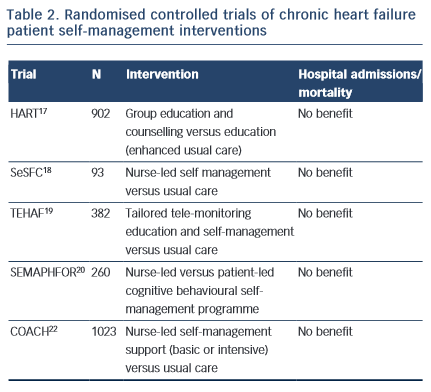

Specialist programmes were introduced to address the individual and complex care requirements in CHF and to encourage patient self- management. The HART trial17 targeted patient capacity and willingness to self-care through group education and counselling to optimise “self-monitoring, environmental restructuring, elicitation of support from family and friends, cognitive restructuring and the relaxation response” (p. 1333). A total of 902 CHF patients were randomised to an education and counselling programme or to education alone (enhanced standard care). Outcomes were assessed after 12 months; the study did not show a benefit of self-management counselling on mortality or hospital readmissions compared to education alone. Shao et al18 found that CHF patients who were randomised to a 12-week nurse-led self-management programme, which emphasised patient self-efficacy to control sodium and fluid intake (SeSFC), showed significantly better symptom control and management than usual care patients, but that both groups had similar health service utilisation. In the TEHAF study, Boyne et al19 randomised CHF patients to a tailored tele-monitoring education and self-care programme or to usual care. No significant differences in hospital admissions or length of stay in hospital were observed between groups over a 12-month period. Smeulders et al20 found that the self-care benefits of a 6-week nurse-led CHF self-management programme were no longer evident six months post-treatment compared with patients who had been randomised to usual care. The SEMAPHFOR trial21 found no difference in hospital admissions/readmissions, self-care, or quality of life between CHF patients randomised to either a nurse-led or patient-led cognitive behavioural self-management programme.

Self-management interventions are often embedded within theoretical frameworks, such as Bandura’s social cognitive theory, that emphasise patient self-efficacy (i.e. perceived capacity to meet behavioural challenges) as fundamental to behaviour change. Research evidence to support a pivotal role for self-efficacy in the clinical outcomes of CHF self-management is, however, limited. The COACH trial22 randomised 10 CHF patients23 to one of two specialist CHF nurse support programmes (basic or intensive) or to usual care. CHF nurses were trained to optimise patient self-efficacy and patients were engaged in behavioural modification strategies. The study failed to identify a benefit of treatment on mortality or hospital readmission compared with usual care.

Taken together, these findings suggest that interventions designed to support patient self-management may improve symptom monitoring and compliance,6 but fall short of reducing mortality risk or hospital admissions. While it is possible that such symptoms may not be adequate markers of CHF exacerbation,23 poor patient engagement in self-management interventions probably explains at least some of the limited efficacy of such programmes. To our knowledge, the extent to which patient engagement may have been undermined by known psychosocial confounders, such as depression, has not been reported and would be a useful addition to future research.

Nevertheless, there will always be some inherent limitations. Symptom and weight changes are generally the results of fluid retention and volume overload. However, volume changes tend to be consequent to pressures changes and therefore could be a relatively late indicator for mandating management changes, such as changes in diuretic dosage. A new approach has been to use implanted devices for measuring pressure change. Examples include devices that can directly measure left atrial pressure or pulmonary artery pressure. Monitoring of pulmonary pressure, for example, provides important information at least a couple of days before changes in patient weight are apparent. Thus, a change in diuretic dosage can be instituted earlier and this has been demonstrated to be effective in significantly reducing heart failure hospital admissions.23 This kind of direct monitoring still involves some degree of patient collaboration and self-monitoring, with the patient being given instructions based on the measured pressures. However, in the future, devices are only likely to be used in selected individual patients.