MINOCA Definition

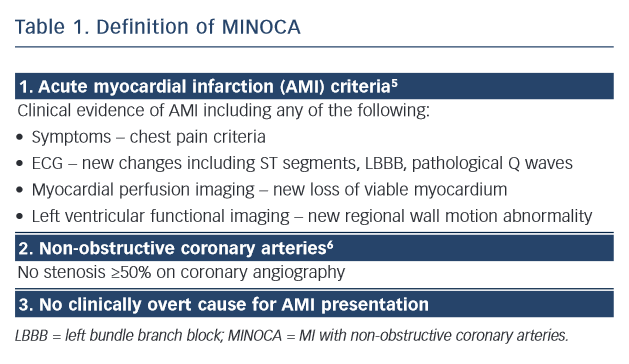

The diagnosis of MINOCA requires: (1) clinical documentation of a myocardial infarct, (2) the exclusion of obstructive CAD and (3) no overt cause for the AMI presentation, such as cardiac trauma (Table 1). Accordingly, the diagnosis is usually made following invasive coronary angiography in the evaluation of an apparent AMI. The diagnostic criteria for AMI are universally established and focus on a significant increase in troponin levels associated with clinical markers of ischaemia.5 Conventionally, obstructive  CAD is defined as an epicardial artery stenosis ≥50 %6 on angiography, thus a stenosis <50 % is required for the diagnosis of MINOCA.

CAD is defined as an epicardial artery stenosis ≥50 %6 on angiography, thus a stenosis <50 % is required for the diagnosis of MINOCA.

Although the diagnostic criteria for MINOCA are specific, it should not be considered a final diagnosis but a ‘working diagnosis’ whose underlying aetiology requires further evaluation. This is similar to the diagnosis of heart failure, where the aetiology responsible needs to be determined rather than just demonstration of ventricular dysfunction.

Aetiology

The mechanism responsible for AMI involves an interaction between atheroma, thrombosis and vascular dysfunction. Given the limited burden of atherosclerosis in MINOCA, it would be expected that atheroma would play a small role in the pathogenesis of the infarct; hence, the focus should be on other potential mechanisms (Table 2). Previous studies have implicated spasm,7 microvascular dysfunction8 and thrombophilic states (Factor V Leiden,9–11 protein C deficiency12 and malignancy-associated thrombophilia13). DaCosta et al. reported that a third of patients with MINOCA had evidence of coronary spasm or thrombotic disorders.10

Furthermore, non-ischaemic causes of MINOCA must also be considered. Several disorders that result in myocardial injury may mimic ischaemic MI and fulfil the universal criteria for AMI. Acute myocarditis, pulmonary embolism and some cardiomyopathies14,15 are examples of disorders that may mimic AMI. Delineating these aetiologies is paramount since it will impact on the appropriate management of these patients.

Prevalence

The reported prevalence of MINOCA varies depending on the data collection methods and definitions used. For example, data from large AMI registries with consecutive patient recruitment report a prevalence of 1–4 % when the definition is restricted to completely normal coronaries (0 % stenosis);13,16 however, if a <50 % stenosis threshold is used, the prevalence has been reported as 5–14 %.3,17,18 A recent systematic review of the published literature using a <50 % stenosis threshold for MINOCA reported a prevalence of 6 % (95 %CI: 5–7 %).4

Clinical Presentation

As the working diagnosis of MINOCA is typically made following coronary angiography, some clinically overt non-ischaemic causes of the apparent AMI presentation will be immediately evident. For example, direct cardiac trauma resulting in myocardial injury with associated ECG changes and increased troponin levels should not be diagnosed as MINOCA if angiography is underta ken to document the underlying coronary anatomy. Similarly, classical apical ballooning on left ventriculography with non-obstructive coronary arteries on angiography should be diagnosed as takotsubo cardiomyopathy rather than MINOCA. This exclusion of patients with overt clinical causes for their AMI presentation is consistent with the principle of MINOCA as a working diagnosis, necessitating the determination of the underlying cause.

ken to document the underlying coronary anatomy. Similarly, classical apical ballooning on left ventriculography with non-obstructive coronary arteries on angiography should be diagnosed as takotsubo cardiomyopathy rather than MINOCA. This exclusion of patients with overt clinical causes for their AMI presentation is consistent with the principle of MINOCA as a working diagnosis, necessitating the determination of the underlying cause.

In patients with clinical markers of an AMI in the absence of obstructive CAD and no overt underlying cause for their presentation (Table 1), a diagnosis of MINOCA should be made and the potential causes (as listed in Table 2) considered. A systematic review of the published literature comparing the clinical characteristics of AMI with and without obstructive CAD revealed that patients with MINOCA (a) tended to be younger, (b) were more frequently women, but (c) had a similar cardiovascular risk profile.4 Thus, distinguishing a patient with MINOCA from those with obstructive CAD on the basis of the clinical presentation and characteristics alone is not possible.

Prognosis

The prognosis of MINOCA is often considered benign by clinicians given the absence of obstructive CAD. However, contemporary data suggest that the prognosis is more guarded with some large studies reporting an all-cause mortality rate of 1.1–2.6 % at 30 days and 3.3–6.4 % at 12 months.13,19 Furthermore, a Korean AMI registry that evaluated 12-month all-cause mortality rates in 8,510 consecutive AMI patients reported rates of 3.1 % in those with MINOCA and 3.2 % in those with single- or double-vessel obstructive CAD.20

Diagnostic Measures

When using the working diagnosis of MINOCA to assess the underlying cause, the first step is to exclude non-cardiac pathology responsible for the raised troponin levels (and thus incidental nonobstructive coronaries). Examples include pulmonary embolism and renal impairment (as discussed below). Thereafter, cardiac causes should be considered, including disorders associated with: (a) structural myocardial dysfunction and (b) ischaemic myocardial damage (Table 2).