Long QT syndrome

Long QT syndrome represents a collection of mostly autosomal dominantly inherited disorder of ion channels in the electrical pathways of the heart. They manifest themselves through prolongation of the QT interval on the ECG, which can vary significantly from day to day and in response to environmental factors, such as drug administration. They can present with VT, particularly polymorphic VT (see below), or with sudden death.

Normal QT interval is 450 ms at a heart rate of 60bpm. The QT interval progressively shortens with heart rates above 60bpm, and lengthens with heart rates below this number; therefore, a correction formula is used to provide the QTc, which also has a normal cut-off of 450ms. The most commonly used formula, the Bazett formula is:

QTc= QT/[square root of(R-R interval in seconds)]

Most ECG computers perform this, but can be inaccurate at ascertaining the end of the T wave and a beginning of the u wave, which can follow a T wave in normal people, as well as in pathological conditions.

Long QT patients may require implantation of a defibrillator, though treatments, drug or otherwise, vary according to the sub-type and the individual’s personal and family history. A family history of sudden death, or a personal history of syncope are bad prognostic signs. B- Blockers are the most appropriate drug for the majority of long QT syndromes, though not all.

Brugada syndrome

This is another of the inherited ion channel disorders with its own specific phenotype. It is a significant cause of sudden death in the young, and drug treatments to prevent VT or VF are ineffective. Patients will usually require a defibrillator.

The characteristic ECG abnormalities are the mainstay of diagnosis. They are those of a partial RBBB with ST elevation in leads V1, V2 and V3. These ECG changes can fluctuate markedly, sometimes being completely absent, sometimes being marked and highly abnormal. The introduction of a class Ic antiarrythmic such as flecainide or ajmaline, can expose these changes markedly and is used as a diagnostic test only by expert cardiac specialist teams (with full resuscitation facilities and an EP lab nearby!)

Dizzy spells and syncope in the young are usually vasovagal episodes and are usually benign. However, the presence of a short PR interval with a delta wave in such patients mandates urgent investigation. The normal AV node slows conduction between the atria and the ventricles. An accessory pathway, as found in WPW, can occasionally conduct atrial depolarisations at very high rates to the ventricle, meaning that a bout of AF can induce VF. This is rare even by the standards of WPW (sudden death rate of those with WPW approx 0.1-0.4%). However, when it is considered that up to 1 in 300 of the population may have this condition, that figure gains more significance.

The drug of choice for WPW is flecainide, which selectively blocks the accessory pathway. AV nodal blocking agents can potentially make the problem worse in isolation.

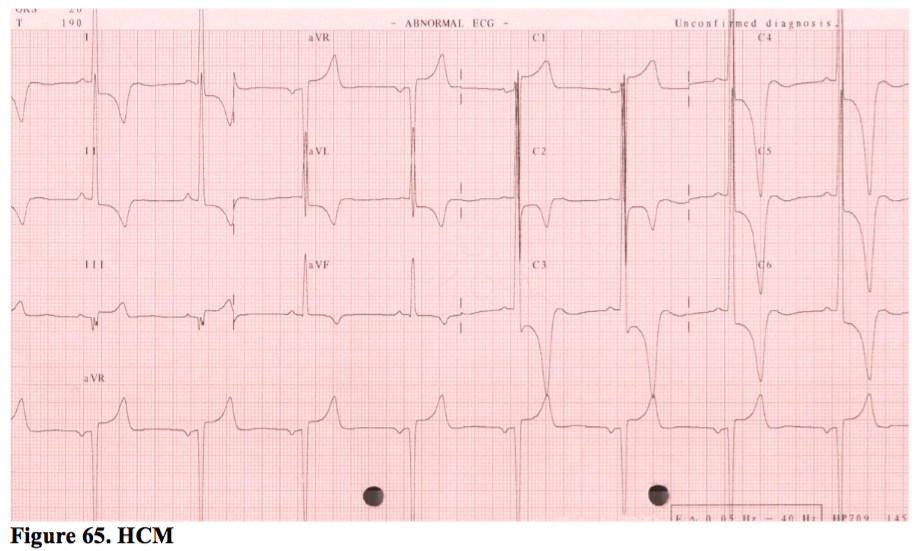

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

This is another collection of inherited disorders, most of which are autosomal dominant. HCM can affect any part of the cardiac myocyte structure, producing abnormal muscle, which classically has a pattern of ‘disarray’. Symptoms include AF, VT, syncope and heart failure. They are at increased risk of sudden death.

Unfortunately, not all HCM ECGs look as obvious as the one shown in Figure 65 - far from it. Any abnormality of the resting ECG in the context of a first degree relative with HCM may reflect the expression of the gene and an increased risk of sudden death. Anyone suspected of having the gene or the clinical condition requires a series of investigations (48 hour Holter, ETT, echo, family profiling and more) in order to diagnose and risk stratify with respect to sudden death. Those at high risk may be offered an ICD.

Drugs

Both prescribed and non-prescribed drugs may cause life-threatening complications. Long QT syndrome may only present after prescription of an anti-psychotic, for example. Equally, a history of cocaine abuse may cause episodes of coronary spasm which mimic an acute STEMI, or it may cause accelerated atherosclerosis and a true acute coronary syndrome. Chest pain in the context of ST elevation after cocaine use should be treated with IV benzodiazepines and calcium antagonists; the patient should then be transferred for primary PCI.

Supported by SimpleEducation.co