Prevalence of IAB

In an in-hospital population, Spodick, using as a criterion of IAB the presence of P wave ≥100 ms, identified the prevalence of IAB (most likely partial IAB) in 47 % of the screened population (1,000 patients), being highly prevalent in the subgroup above 60 years of age15.

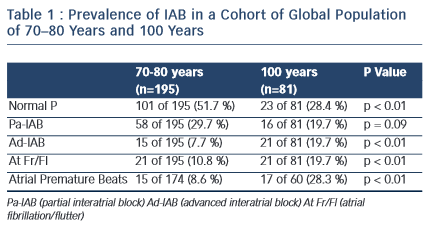

The prevalence of partial (P) and advanced A–IAB is rare before the age of 50. In our experience8 (see Table I), the prevalence is much higher with advancing age. In centenarians the prevalence of A-IAB is higher than that of P-IAB. Also ageing increases the prevalence of AF/Afl, being 10 % at ages 70–80 and 26 % in centenarians.

Recently, we have found in patients with heart failure a prevalence of A-IAB of 10 %9.

Identification of the Syndrome

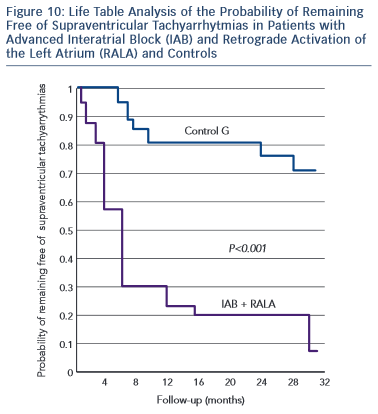

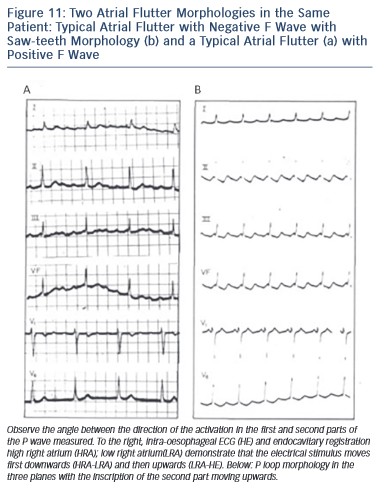

Bayés de Luna et al10 reported on a single sample of patients with long-term follow-up to better characterise the incidence of atrial tachyarrhythmias in patients with advanced IAB (16 patients) and compared them with patients with partial IAB (22 patients) but similar echocardiographic parameters. Th e advanced IAB group presented a higher incidence of atrial flutter/fibrillation (15/16, 93.7 %) during a 30-month follow-up compared with the control group with partial IAB (6/22, 27.7 %) (p < 0,0001). At one year of follow-up, the incidence of arrhythmias was 80 % and 20 % respectively (see Figures 10 and 11).

e advanced IAB group presented a higher incidence of atrial flutter/fibrillation (15/16, 93.7 %) during a 30-month follow-up compared with the control group with partial IAB (6/22, 27.7 %) (p < 0,0001). At one year of follow-up, the incidence of arrhythmias was 80 % and 20 % respectively (see Figures 10 and 11).

Additionally, Holter monitoring showed that the prevalence of frequent premature atrial contractions (more than 60/h) was much more frequent in advanced (75 %) than in partial (25 %) IAB.

In 1998 Bayés de Luna, et al published a review paper in which they summarised all previous research published in this topic; suggesting that the association between advanced IAB and atrial tachyarrahythmias constitute a true syndrome14.

Since then, different groups have confirmed this association16–18 and a recent consensus on IAB has accepted the diagnostic criteria and clinical association of advanced IAB with atrial arrhythmias3. This association is now considered a unique syndrome that sho uld be known as Bayes’ Syndrome19,21.

uld be known as Bayes’ Syndrome19,21.

Should we Prevent Atrial Arrhythmias in Patients with IAB?

The strong relationship between advanced IAB and atrial flutter/ fibrillation led us to investigate the possible role of preventing atrial arrhythmias using antiarrhythmic drugs22. A small comparative trial of patients with advanced IAB received either an antiarrhythmic drug or a placebo. A significant reduction of AF recurrences was observed at follow-up in the group receiving prophylactic antiarrhythmic medication. Despite the small sample, this study should be considered pioneering by suggesting the treatment of patients early on when advanced IAB is detected, in order to reduce the incidence of atrial arrhythmias. This hypothesis needs to be confirmed with larger studies and samples.

We have not tested the possible benefits of antithrombotic therapy in this group of advanced IAB, as currently, the presence of documented AF is still needed, to start anticoagulation medication. However, as an interesting hypothesis, it could be reasonable to consider anticoagulation if the patient presents with advanced IAB and a CHA2DS2-vasc score 3 and the patient presents with advanced IAB. The evidence on the one hand shows that in patients with A-IAB there is an LA disfunction with important electromechanical changes23 and on the other that in many instances the AF is a risk factor but not the actual cause of stroke24 and it may be important to consider the possibility of treatment with antithrombotic therapy in patients with A-IAB and a CHA2DS2-vasc score 3, especially if they show atrial arrhythmias in Holter monitoring. This suggested hypothesis needs to be tested before making any convincing recommendations.

However, several studies with poor results have tried to resynchronise the atria with bi-atrial pacing. There is still no consensus whether this technique reduces the incidence of AF and this technique did not prove to be superior to sequential pacing3.