Dosing, Low-density Lipoprotein levels and Statin Intolerance

LDL-C targets have been abandoned in the ACC/AHA guidelines and instead using fixed doses of high and moderate intensity statins are recommended. The intensity of the statin dose is matched to the person’s baseline ASCVD risk. Although these guidelines make no recommendations for or against targeting specific LDL levels, they do suggest follow up assessment of the lipid panel to assess compliance.6,26 In contrast, the ESC/EAS guidelines approach cholesterol management with targeted LDL-C levels for specific disease states and have no specific statin intensity recommendations.5

Statin-associated Myalgias

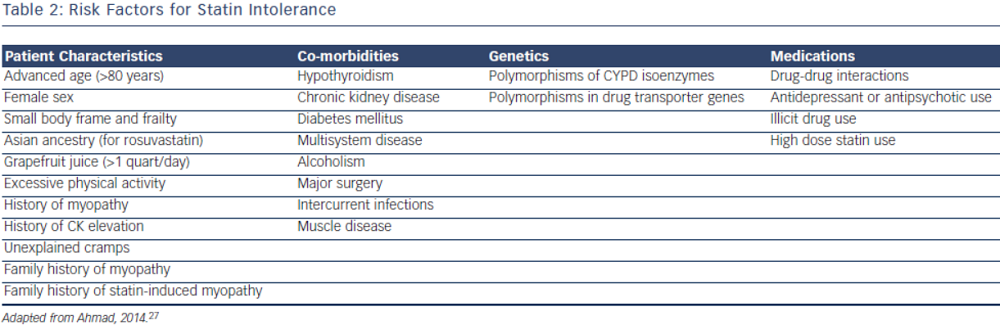

Statin intolerance or the inability to continue statins due to adverse symptoms or abnormal lab values occurs in roughly 5–10 % of patients who use statins. There are only a  limited number of studies on statin intolerance creating a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to prescribers.27 Observational studies like the Prediction of Muscular Risk in Observational conditions (PRIMO) survey, which included 7,924 patients on high dose statins in the outpatient setting found 10.5 % of patients developed muscular symptoms, with the average onset of symptoms being ~1 month after initiation of the statin.28 However, the incidence of reported statin intolerance is greatly variable and thus far randomised clinical trials of statins versus placebo have not shown major differences in symptoms.29,30 Most statin intolerance due to muscle symptoms is related to myalgias, defined as muscle aches without creatinine kinase CK elevation, but rarely patients have developed clinically significant myopathies. Several risk factors have been identified for statin intolerance (see Table 2) and though there is no clear consensus on management of statin intolerance, several small studies have explored this issue. For patients with frank rhabdomyolsis statin therapy should be discontinued.27 For patients with muscle symptoms but normal enzymes the ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines recommend withdrawal and rechallenge with statin.

limited number of studies on statin intolerance creating a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge to prescribers.27 Observational studies like the Prediction of Muscular Risk in Observational conditions (PRIMO) survey, which included 7,924 patients on high dose statins in the outpatient setting found 10.5 % of patients developed muscular symptoms, with the average onset of symptoms being ~1 month after initiation of the statin.28 However, the incidence of reported statin intolerance is greatly variable and thus far randomised clinical trials of statins versus placebo have not shown major differences in symptoms.29,30 Most statin intolerance due to muscle symptoms is related to myalgias, defined as muscle aches without creatinine kinase CK elevation, but rarely patients have developed clinically significant myopathies. Several risk factors have been identified for statin intolerance (see Table 2) and though there is no clear consensus on management of statin intolerance, several small studies have explored this issue. For patients with frank rhabdomyolsis statin therapy should be discontinued.27 For patients with muscle symptoms but normal enzymes the ACC/AHA cholesterol guidelines recommend withdrawal and rechallenge with statin.

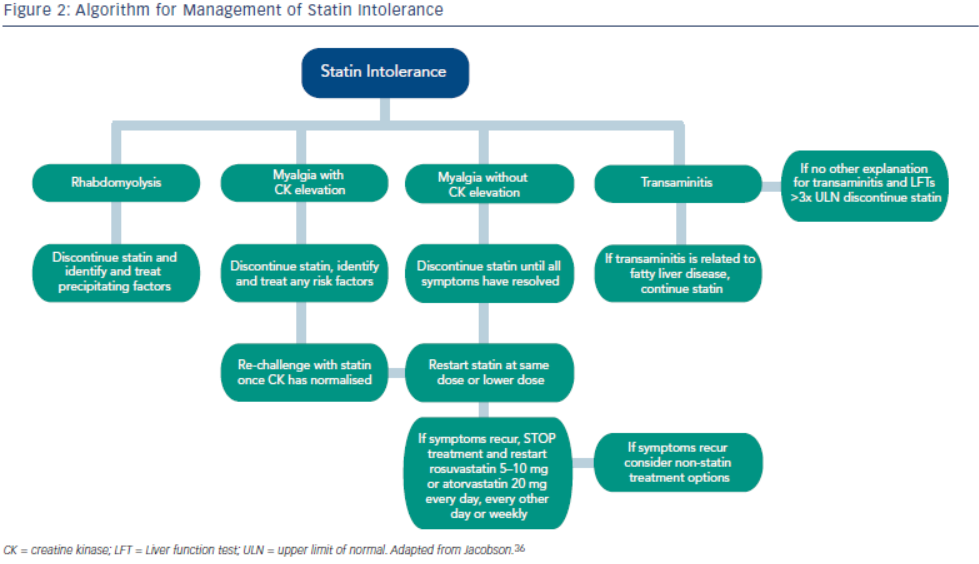

The patients should be rechallenged with statin only after all muscular symptoms have resolved, which may take >2 weeks.6,27 With regard to rechallenging, Glueck et al.31 found that 60/61 patients enrolled tolerated rosuvastatin 5 or 10 mg daily. Similarly, another study by Stein et al.32 enrolled patients who had discontinued statins in the past due to muscle-related side effects or those who were currently on statin therapy but had impaired quality of life, they found that 97 % of patients tolerated fluvastatin. In addition to switching statin therapy, there has been investigation into alternate doing strategies. A retrospective analysis by Backes et al. found that 72.5 % of the patients tolerated every other day 5–10 mg rosuvastatin.33 Kennedy et al. found that 80 % patients tolerated once weekly 5 or 10 mg of rosuvastatin.34 Simvastatin 80 mg should be avoided in general due to increased risk of myopathy and lack of incremental efficacy compared to lower doses.35 Algorithms for managing patients with statin intolerance may facilitate decision-making in the clinic (see Figure 1).36

The patients should be rechallenged with statin only after all muscular symptoms have resolved, which may take >2 weeks.6,27 With regard to rechallenging, Glueck et al.31 found that 60/61 patients enrolled tolerated rosuvastatin 5 or 10 mg daily. Similarly, another study by Stein et al.32 enrolled patients who had discontinued statins in the past due to muscle-related side effects or those who were currently on statin therapy but had impaired quality of life, they found that 97 % of patients tolerated fluvastatin. In addition to switching statin therapy, there has been investigation into alternate doing strategies. A retrospective analysis by Backes et al. found that 72.5 % of the patients tolerated every other day 5–10 mg rosuvastatin.33 Kennedy et al. found that 80 % patients tolerated once weekly 5 or 10 mg of rosuvastatin.34 Simvastatin 80 mg should be avoided in general due to increased risk of myopathy and lack of incremental efficacy compared to lower doses.35 Algorithms for managing patients with statin intolerance may facilitate decision-making in the clinic (see Figure 1).36

Statin-associated Transaminitis

Elevations of serum alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase up to 3x the ULN transaminitis is also seen with statin users in 0.5–3 % of patients.37 In a post hoc analysis of the Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary Heart Disease Evaluation (GREACE) study population, 437 patients with baseline elevation of liver enzymes, thought to be related to fatty liver disease, were randomised to placebo versus statin therapy. The authors found an improvement of liver enzymes and 68 % risk reduction of cardiovascular events in the group treated with statin therapy.38 Similarly in a post hoc analysis of the Incremental Decrease in Events through Aggressive Lipid Lowering (IDEAL) study, authors found that 1,081 patients with ALT>Upper Limit of Normal (ULN) had a significant risk reduction when treated with high intensity statin versus low intensity statin.39 The current 2013 ACC/AHA Cholesterol guidelines recommend evaluating baseline assessment of liver enzymes but no routine follow up. These observational data support the safety of statins in patient with mild elevations of liver enzymes; however, if LFTs are elevated to >3 times the ULN, with no other explanation, the statin therapy should be discontinued.6,27

Statin-associated Hyperglycaemia

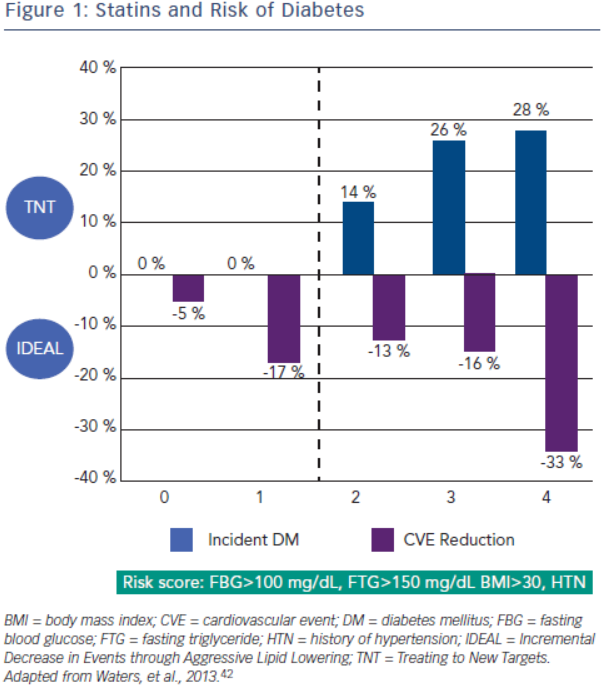

Increased incidence of diabetes is associated with statin use. A meta-analysis by Sattar et al., which included 91,140 patients found a 9 % increase in incident diabetes with statin use, and in another meta-analysis by Preiss et al., authors were able to show an increased risk with more intensive therapy.40,41 Risk factors for developing diabetes during statin therapy are fasting blood glucose >100 mg/ dL, fasting triglycerides >150 mg/dL, BMI >30 and hypertension. In a recent study, Waters et al. assessed the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular event reduction from patients in the Treating to New Targets (TNT) and IDEAL studies. They concluded high intensity statins increased the risk of diabetes in patients with 2–4 risk factors but there was no increased risk in patient with 0–1 risk factors. However, in both groups statin therapy was associated with substantial risk reduction with the highest benefit in the patients with the most risk factors for developing diabetes (see Figure 2).42 Analysis from the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER), which randomised 17,603 patients without cardiovascular disease or diabetes to placebo versus rosuvastatin 20 mg demonstrated increased risk of incident diabetes in the statin group. Ridker et al. concluded overall benefit of statins on cardiovascular events and mortality exceeded the hazard of diabetes.43 A recent meta-analysis studied the effects of two genetic variants of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), the target enzyme inhibited by statins, on body weight and risk of diabetes. Authors also updated their previous meta-analysis on association of statins and diabetes. The study concluded that both genetic variants and statin treatment were associated with weight gain and diabetes.44

Increased incidence of diabetes is associated with statin use. A meta-analysis by Sattar et al., which included 91,140 patients found a 9 % increase in incident diabetes with statin use, and in another meta-analysis by Preiss et al., authors were able to show an increased risk with more intensive therapy.40,41 Risk factors for developing diabetes during statin therapy are fasting blood glucose >100 mg/ dL, fasting triglycerides >150 mg/dL, BMI >30 and hypertension. In a recent study, Waters et al. assessed the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular event reduction from patients in the Treating to New Targets (TNT) and IDEAL studies. They concluded high intensity statins increased the risk of diabetes in patients with 2–4 risk factors but there was no increased risk in patient with 0–1 risk factors. However, in both groups statin therapy was associated with substantial risk reduction with the highest benefit in the patients with the most risk factors for developing diabetes (see Figure 2).42 Analysis from the Justification for the Use of Statins in Prevention: an Intervention Trial Evaluating Rosuvastatin (JUPITER), which randomised 17,603 patients without cardiovascular disease or diabetes to placebo versus rosuvastatin 20 mg demonstrated increased risk of incident diabetes in the statin group. Ridker et al. concluded overall benefit of statins on cardiovascular events and mortality exceeded the hazard of diabetes.43 A recent meta-analysis studied the effects of two genetic variants of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), the target enzyme inhibited by statins, on body weight and risk of diabetes. Authors also updated their previous meta-analysis on association of statins and diabetes. The study concluded that both genetic variants and statin treatment were associated with weight gain and diabetes.44