Antiplatelet Drugs in Hypertension

As hypertension is associated with increased intravascular pressure, most of the expected complications should be of haemorrhagic origin; however, most of the hypertension-related complications in developed countries are nowadays thrombotic ones, with CHD and ischaemic stroke being the most prevalent events. In addition, some hypertension complications such as heart failure or atrial fibrillation are themselves associated with increased risk of stroke and thromboembolism. Therefore, antithrombotic therapy should possibly reduce thrombotic complications in hypertensive patients.

Hypertension Optimal Treatment

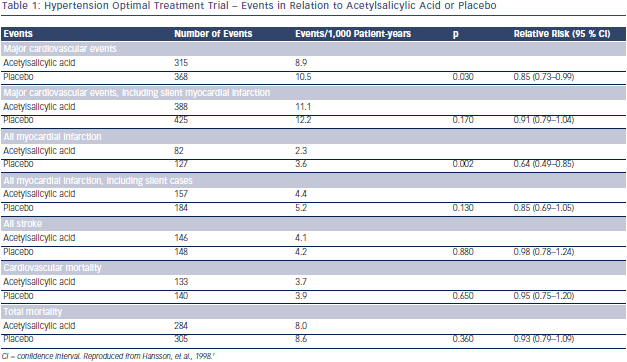

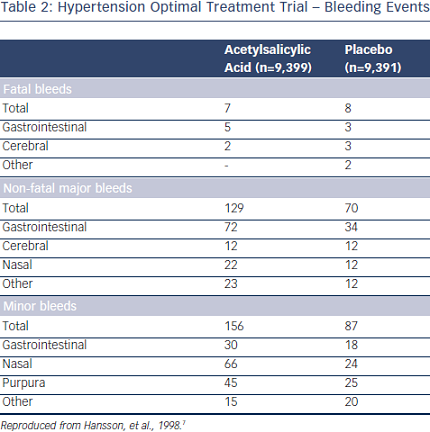

So far the only study assessing the potential benefit of a low dose of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) in hypertension is the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT)  randomised trial.7 A total of 18,790 patients aged 50–80 years were randomly assigned to three target diastolic blood pressures: ≤90 mmHg, ≤85 mmHg and ≤80 mmHg. Within each group, the patients were randomised to 75 mg/day ASA or placebo. Low-dose ASA reduced major CV events and all myocardial infarctions (see Table 1). Fatal bleeds including cerebral ones did not differ in the two groups but non-fatal major and minor bleeds were significantly more frequent among patients receiving ASA than in those taking placebo (see Table 2).

randomised trial.7 A total of 18,790 patients aged 50–80 years were randomly assigned to three target diastolic blood pressures: ≤90 mmHg, ≤85 mmHg and ≤80 mmHg. Within each group, the patients were randomised to 75 mg/day ASA or placebo. Low-dose ASA reduced major CV events and all myocardial infarctions (see Table 1). Fatal bleeds including cerebral ones did not differ in the two groups but non-fatal major and minor bleeds were significantly more frequent among patients receiving ASA than in those taking placebo (see Table 2).

Before the publication of the HOT study, hypertension was often considered a contraindication to ASA because of the potentially increased risk of bleeding (cerebral in particular).7

A later publication from the HOT study showed gender differences in the preventive effect of ASA, which significantly reduced myocardial infarction only in men by 42 %; but the reduction in myocardial infarction was only 19 %, and thus not significant in women. This was due to less statistical power when subdivided into men and women.8

Subgroup-treatment interaction analyses indicated that only patients with serum creatinine >1.3 mg/dl had a significantly greater reduction of CV events and myocardial infarction, while the risk of bleeding was not significantly different between the subgroups.9 A favourable balance between benefit and harm of ASA was documented in subgroups of patients at higher global baseline risk and baseline systolic blood pressure (≥180 mmHg).

More recently, the benefit of ASA was significantly greater in a subgroup with low estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) (<45 ml/min/1.73 m2), for which an increased risk of major bleeding appears to be outweighed by substantial benefit.10

Cochrane Collaboration Review of Antiplatelet Agents For Hypertension

Lip et al. found four trials including a total of 44,012 patients to be subject of the meta-analysis.11 ASA did not reduce stroke or all CV events compared with placebo in primary prevention patients with elevated blood pressure and no prior CV disease. On the other hand, myocardial infarction was reduced with ASA in primary prevention; however, the benefit was negated by harm of similar magnitude due to an increase in major haemorrhage.

No benefit for warfarin therapy alone or in combination with ASA was found in patients with elevated blood pressure. Diclopidine, clopidogrel and newer antiplatelet agents (prasugrel, ticagrelor) have not been sufficiently evaluated in patients with hypertension.

There is a need for further trials evaluating antithrombotic therapy, including newer agents in hypertension.

2013 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology Guidelines

The 2013 European Society of Hypertension (ESH)/European Society of Cardiology guidelines12 concluded that antiplatelet therapy, particularly low-dose ASA, should be prescribed to controlled hypertensive patients with previous CV events and should be considered in hypertensive patients with reduced renal function or a high CV risk. ASA is not recommended in low-to-moderate risk hypertensive patients in whom absolute benefit and harm are equivalent.

Acetylsalicylic Acid in Preventing Pre-eclampsia

Pre-eclampsia (defined as de novo appearance of hypertension in pregnancy accompanied by proteinuria >0.3 g/24 hours) is associated with increased risk of maternal, foetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. A reliable prediction of development of this condition has so far failed.

Pre-eclampsia (defined as de novo appearance of hypertension in pregnancy accompanied by proteinuria >0.3 g/24 hours) is associated with increased risk of maternal, foetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality. A reliable prediction of development of this condition has so far failed.

A meta-analysis by Duley et al.13 showed only a mild risk reduction of developing pre-eclapmsia with low-dose ASA. Therefore, low-dose of ASA was only recommended in pregnant women at high risk of developing pre-eclampsia defined as a history of pre-eclampsia presenting before 28 weeks of gestation.14

In 2010, Bujold et al. pooled data from over 11,000 women enrolled in randomised controlled trials evaluating low-dose ASA in the treatment of pregnant women at moderate or high risk for preeclampsia.15 They concluded that women who initiated treatment at less than 16 weeks of gestation had a relative risk (RR) of 0.47 (confidence interval [CI] 0.34–0.65) for developing pre-eclampsia, and a 0.09 RR (CI 0.02–0.37) for developing severe pre-eclampsia compared with controls.

Women at high risk of pre-eclampsia (hypertension in a previous pregnancy, chronic kidney disease, autoimmune disease such as systemic lupus erythematosus or antiphospholipid syndrome, type 1 or 2 diabetes, chronic hypertension) or with more than one moderate risk factors for preeclampsia (first pregnancy, age ≥40 years, pregnancy interval of >10 years, body mass index (BMI) ≥35 kg/m2 at first visit, family history of pre-eclampsia and multiple pregnancy) are advised to take 75 mg of ASA daily from 12 weeks until delivery.16