Studies in Blood Pressure – Large Clinical Outcome Trials

Statins and Blood Pressure – Implications of Large Clinical Outcome Trials

Treatment of hypertension is associated with a reduction in stroke and, to a lesser extent, coronary events. It is also well-known that elevated serum total cholesterol significantly increases CHD risk. Therefore, it is logical that co-existing vascular risk factors including abnormal lipid profiles should be an integral part of hypertension management.

The benefit of lowering both BP and cholesterol was evaluated in two large-scale trials: Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack  Trial (ALLHAT)29 and Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial - Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA).30

Trial (ALLHAT)29 and Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial - Lipid-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-LLA).30

Part of ALLHAT was designed to determine whether pravastatin compared with usual care would reduce all-cause mortality in 10,355 patients with hypertension and moderate hypercholesterolaemia, plus at least one additional CHD risk factor.29 At four years, total cholesterol was reduced by 17.2 % with pravastatin versus 7.6 % with usual care. All-cause mortality was similar in the two groups and CHD event rates were not different between the two groups; six-year CHD event rates were 9.3 % (pravastatin) and 10.4 % (usual care). These results could be attributed to the small difference in total cholesterol (9.6 %) and LDL-cholesterol (16.7 %) between pravastatin and usual care compared with other statin trials. Adherence to the treatment assigned declined over time. For those assigned to pravastatin, adherence dropped from 87.2 % at year two to 80 % at year four, and 77 % at year six, although the number of participants was small. On the other hand, in the usual care group, crossovers to statin treatment increased from 8 % at year two to 17 % by year four. This increase continued at year six, but the number of participants was small.

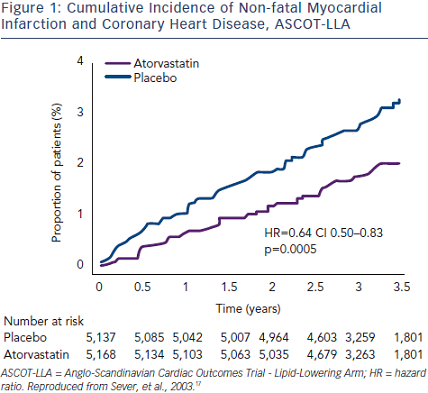

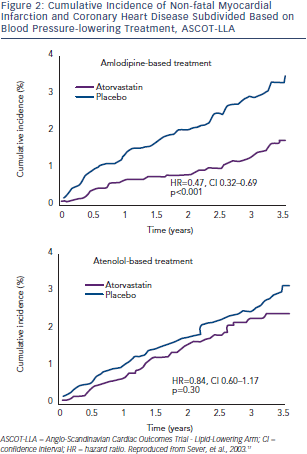

In the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial - Blood Pressure-Lowering Arm (ASCOT-BPLA) trial,30 19,342 men and women with hypertension and at least three other CV risk factors were randomised to amlodipine (5–10 mg/d) ± perindopril (4–8 mg/d) or to atenolol (50–100 mg/d) ± bendroflumethiazide (1.25–2.5 mg/d). A total of 10,305 of these patients with normal or slightly elevated total cholesterol were randomised to atorvastatin 10 mg/d or placebo.17 The atorvastatin arm was stopped prematurely at 3.3 years  due to a significant reduction in the primary endpoint (-36 %; p=0.0005) (see Figure 1). The benefit of atorvastatin treatment was apparent within the first year of treatment. Fatal/ non-fatal stroke and total CV/coronary events were also reduced with atorvastatin. At one year, atorvastatin reduced total cholesterol by 24 % and LDL-cholesterol by 35 %. However, in the period between six weeks and 18 months, a significant 1.1/0.7 mmHg difference in BP was seen in favour of atorvastatin regardless of titration of doses and numbers of drugs. Overall, amlodipine-perindopril therapy was superior to atenolol-bendroflumethiazide therapy,30 and a further analysis of early monotherapy data comparing amlodipine with atenolol suggested a positive interaction between atorvastatin and amlodipine.31 Compared with placebo, allocation to atorvastatin reduced the incidence of the primary endpoint significantly by 53 % (hazard ratio [HR] 0.47; 95 % CI 0.32–0.69; p<0.0001) among those allocated the amlodipine-based regimen, whereas it reduced the incidence of this outcome by only 16 % (HR 0.84; 95 % CI 0.60–1.17; p=0.30). The difference between these risk reductions with atorvastatin was of borderline significance (heterogeneity; p=0.025) (see Figure 2).

due to a significant reduction in the primary endpoint (-36 %; p=0.0005) (see Figure 1). The benefit of atorvastatin treatment was apparent within the first year of treatment. Fatal/ non-fatal stroke and total CV/coronary events were also reduced with atorvastatin. At one year, atorvastatin reduced total cholesterol by 24 % and LDL-cholesterol by 35 %. However, in the period between six weeks and 18 months, a significant 1.1/0.7 mmHg difference in BP was seen in favour of atorvastatin regardless of titration of doses and numbers of drugs. Overall, amlodipine-perindopril therapy was superior to atenolol-bendroflumethiazide therapy,30 and a further analysis of early monotherapy data comparing amlodipine with atenolol suggested a positive interaction between atorvastatin and amlodipine.31 Compared with placebo, allocation to atorvastatin reduced the incidence of the primary endpoint significantly by 53 % (hazard ratio [HR] 0.47; 95 % CI 0.32–0.69; p<0.0001) among those allocated the amlodipine-based regimen, whereas it reduced the incidence of this outcome by only 16 % (HR 0.84; 95 % CI 0.60–1.17; p=0.30). The difference between these risk reductions with atorvastatin was of borderline significance (heterogeneity; p=0.025) (see Figure 2).

Despite extensive crossovers from and to statin usage, the RR reduction in primary events among those originally assigned to atorvastatin remained at 36 % (HR 0.64; 95 % CI 0.53–0.78; p<0.0001) (carryover effect) 2.2 years after the end of the ASCOT-BPLA.32

In the UK ASCOT population, all-cause mortality remained significantly lower in those originally assigned atorvastatin (HR 0.86, 95 % CI 0.76–0.98; p<0.02) 11 years after initial randomisation and approximately eight years after closure of the lipid-lowering arm (LLA), which may be due to legacy effect.33

A meta-analysis of large clinical trials, including only those with more than 1,000 patients followed for more than two years, was published by Messerli et al.34 Besides ASCOT-LLA and the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT), 12 trials enrolling 69,284 patients met the inclusion criteria. Overall, in these 12 trials, statin therapy decreased cardiac death by 24 % (RR 0.76; 95 % CI 0.71–0.82). There was no evidence of a difference in RR estimates for hypertensive and normotensive patients. In conclusion, statin therapy effectively decreased CV morbidity and mortality to the same extent in hypertensive and normotensive patients.

2013 European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology Guidelines

The 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines12 recommend using statin therapy in hypertensive patients at moderate-to-high CV risk to achieve the target LDL cholesterol value <3 mmol/l (115 mg/dl). For individuals with manifest CV disease or at very high CV risk35 a more aggressive LDL target of <1.8 mmol/l (70 mg/dl) is recommended.