Patients suffering acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation ( STEMI ) require full attention of the whole STEMI network to save their lives and to improve the quality of life after a heart attack. Close cooperation among all stakeholders on a national and regional level has to be established. The emergency medical service (EMS) and direct transportation to the 24 hours a day, seven days a week(24/7) catheterisation laboratory play a crucial role together with the patient-oriented public education campaigns. The most recent Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology on patients with acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation (ESC STEMI Guidelines) were published in 2012 and covered the complexity of organisational and medical aspects from the emergent diagnosis and treatment until outpatient care. 1 The reason for establishing the Stent for Life Initiative and its ACT NOW. SAVE A LIFE public campaign as a joint initiative of the European Association of percutaneous coronaryintervention ( EAPCI ) and European Percutaneous Cardiovascular Revascularization Course ( EuroPCR ) was the lack of implementation of the Guidelines into the practice across Europe. The incredible achievements in 16 participating countries and organisations can be followed online at www.stentforlife.com and are well documented in the recent publication of Kristensen et al. 2

Atypical electrocardiogram (ECG) presentations that deserve prompt management in patients with signs and symptoms of ongoing myocardial ischaemia include:

The patients with ongoing ischaemic symptoms, even in the absence of ST-segment elevations, should be managed in the same way as the STEMI patients. This recommendation, based more on experience than evidence, may shorten the delay to diagnosis and optimal treatment, and at the same time may decrease the risk of bleeding after the potent antithrombotic medication. A bit provocative is the suggestion of new and simplified classification of acute coronary syndrome with/ without ongoing myocardial ischaemia (ACS w/wo OMI) instead of the currently used STEMI and non-STEMI. Such an approach may better reflect current treatment practice in some catheterisation laboratories (cath labs) and regions with the aim of facilitating the decisions made at the time of the first medical contact (FMC). The target of such simplification is the earliest selection of patients at high clinical risk that should be transported directly to the cath lab or 24/7 primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) centre bypassing any other facility. Widimsky et al.3 defined the ACS w OMI as ongoing (or recurrent) clinical signs of acute myocardial ischaemia (i.e. persistent chest pain and/or dyspnoea at rest) plus at least one of the following:

It is important to keep in mind that isolated findings as listed above (e.g. malignant arrhythmias without any clinical or ECG sign of acuteischaemia) do not fulfil this definition. The high clinical suspicion for acute myocardial infarction is important. Direct transport to the cath lab (bypassing any other location, e.g. intensive care unit or emergency room) is always required in groups 1–4. Patients from groups 5–7 should also be transported to a non-stop (24/7) primary PCI facility (either directly to the cath lab or they may be primarily admitted to theintensive cardiac care unit with the cath lab immediately available). Healthcare systems with multiple organisational issues may especially benefit from such practical recommendations.

Direct transport to the cath lab (bypassing any other location, e.g. intensive care unit or emergency room) is always required in groups 1–4. Patients from groups 5–7 should also be transported to a non-stop (24/7) primary PCI facility (either directly to the cath lab or they may be primarily admitted to theintensive cardiac care unit with the cath lab immediately available). Healthcare systems with multiple organisational issues may especially benefit from such practical recommendations.

Time Intervals From Onset of Symptom Until Effective Treatment

The principle aim of the medical systems in patients with STEMI is to prevent their death and to improve the quality of life after a heart attack. Besides the effective treatment of ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation in the pre-hospital phase, shortening of the total ischaemic time as much as possible is crucial. ‘Patient delay’ and ‘system delay’, where the patient delay means the delay between symptom onset and FMC followed by the system delay until reperfusion therapy.

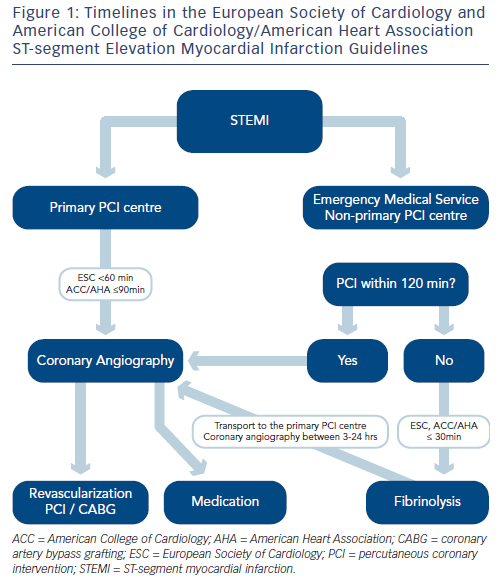

There is one important question with potential clinical consequences: who represents the FMC? Based on the ESC Guidelines, FMC is defined as the point at which the patient is either initially assessed by a paramedic or physician or other medical personnel in the pre-hospital setting, or the patient arrives at the hospital emergency department and therefore often in the outpatient setting.1 According to the time intervals mentioned in the ESC Guidelines, the preferred/ accepted system delay from FMC to the most effective reperfusion strategy (primary PCI, i.e. wire passage) should not exceed 90/120 minutes (min) in most patients and ≤60/90 min in high-risk patients with large anterior STEMI and early presenters within two hours. In case of fibrinolysis, the recommended system delay (FMC to needle) is ≤30 min. The diagnosis of STEMI should be verified within 10 min of FMC, which in fact means that the FMC personnel has to have the 12-lead ECG available. In future, the time of the medical system activation (i.e. the time of the first phone call) should be involved in the time intervals monitoring. The definition of the FMC might be modified to the first phone or personal contact of the patient with any representative of the medical system.

Current recommendation for reperfusion and the difference between the ESC and ACC/AHA4 STEMI Guidelines is described in Figure 1.