Diagnosis

In patients with prior valve replacement, symptoms of CHF or haemolysis should merit further evaluation for PVL. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is  important to establish ventricular function and overall valve assessment. It is important to understand, however, that prosthetic valve shielding may not provide an adequate characterisation of PVL and appropriate diagnosis may require further imaging using transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE). In some rare situations, it may be unclear whether the leak is intra- or paravalvular by both TTE and TOE; intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) may be helpful in these situations.

important to establish ventricular function and overall valve assessment. It is important to understand, however, that prosthetic valve shielding may not provide an adequate characterisation of PVL and appropriate diagnosis may require further imaging using transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE). In some rare situations, it may be unclear whether the leak is intra- or paravalvular by both TTE and TOE; intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) may be helpful in these situations.

Mitral Paravalvular Leak

The ‘clock face’ nomenclature of the mitral valve (MV) as seen from the left atrium, or ‘surgeon’s view’, facilitates communication among different specialists (see Figure 1). Most PVLs occur anteromedially (10 to 11 o’clock position) and posterolaterally (5 to 6 o’clock position).7,10

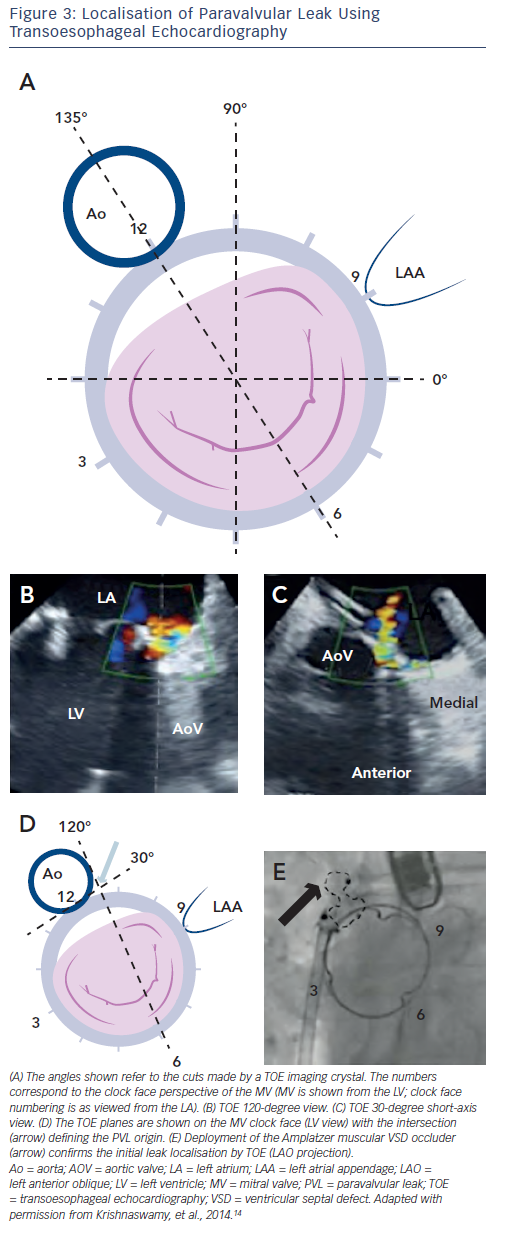

As discussed above, TTE may provide the diagnosis and location of PVL (see Figure 2). However, TOE is usually necessary to define the extent of PVL, and understanding the relationship of TOE angles is imperative to an accurate localisation and subsequent treatment (see Figure 3). Three-dimensional (3D) TOE may be beneficial to localise the PVL, but is sometimes limited by shadowing artifact or echo dropout (see Figure 4).

As discussed above, TTE may provide the diagnosis and location of PVL (see Figure 2). However, TOE is usually necessary to define the extent of PVL, and understanding the relationship of TOE angles is imperative to an accurate localisation and subsequent treatment (see Figure 3). Three-dimensional (3D) TOE may be beneficial to localise the PVL, but is sometimes limited by shadowing artifact or echo dropout (see Figure 4).

Aortic Paravalvular Leak

The clock face of the aortic valve (AV) shares the 12 o’clock position with the MV (see Figure 1). Aortic PVLs are most commonly encountered at the 7 to 11 o’clock position (46 %), followed by the 11 to 3 o’clock position (36 %).10 We find it helpful to also identify the location of the PVL with respect to the native coronary cusp,  which more easily translates to the fluoroscopic relationships with which interventionists are familiar. Figure 5 demonstrates the AV in fluoroscopic projection and TOE.

which more easily translates to the fluoroscopic relationships with which interventionists are familiar. Figure 5 demonstrates the AV in fluoroscopic projection and TOE.

Outcomes of Percutaneous Paravalvular Leak Closure

While a number of groups have demonstrated successful percutaneous PVL closure in small series’ and case reports, Ruiz and colleagues and Sorajja and colleauges have provided the largest published experiences.9 Ruiz and colleagues performed 57 PVL procedures in 43 patients, with a procedural success of 86.0 % and a 30-day all-cause mortality rate of 5.4 %.11 As a point of reference, surgical series’ have demonstrated a mortality of 6 %.6,10 Haemolysis was a common finding, seen as the reason for the procedure in 14 % and in combination with CHF among 70 %. Despite the fact that 35 % of patients actually developed worsening haemolysis after the  procedure, the number of patients requiring erythropoietic agents of regular transfusion decreased from 56 to 5 %. In this series, 10 patients required a redo percutaneous procedure, and two required three procedures total. This not only demonstrates the safety of repeat percutaneous procedures, but the idea that continued valve dehiscence may lead to new or worsening leaks.

procedure, the number of patients requiring erythropoietic agents of regular transfusion decreased from 56 to 5 %. In this series, 10 patients required a redo percutaneous procedure, and two required three procedures total. This not only demonstrates the safety of repeat percutaneous procedures, but the idea that continued valve dehiscence may lead to new or worsening leaks.

Sorajja and colleagues published their short-term outcomes of closure for 141 defects (115 patients, 78 % mitral, 22 % aortic) and long-term outcomes on closure of 154 defects (126 patients).11,13 Heart failure outcomes were substantially improved: despite 93 % of patients presenting with CHF, 72 % had none or minimal dyspnoea at three-year follow-up. Procedural success was enjoyed by 77.0 % of patients, and 8.7 % experienced a major adverse event at 30-days. Importantly, >3+ PVL was seen in only 10 % of patients post-closure. One patient required emergent surgery due to valve interference by a device that could not be retrieved, there were no procedural deaths, and survival was 64 % at three years.

It is difficult to accurately compare survival in the series of percutaneous PVL closure with those in surgical series. As this is a procedure still in its infancy, with surgery often performed without consideration of, or access to, percutaneous closure, those patients presenting for percutaneous therapy are often far more co-morbid than their peers who are taken for surgery. Nevertheless, the available data suggest safety of this approach and substantial functional improvement is enjoyed by patients undergoing percutaneous PVL closure. Given the high risks and poor results of reoperation, percutaneous PVL closure presents a promising treatment that is likely to improve with time and innovation.