Cost-Effectiveness Analysis with Primary Patient Data

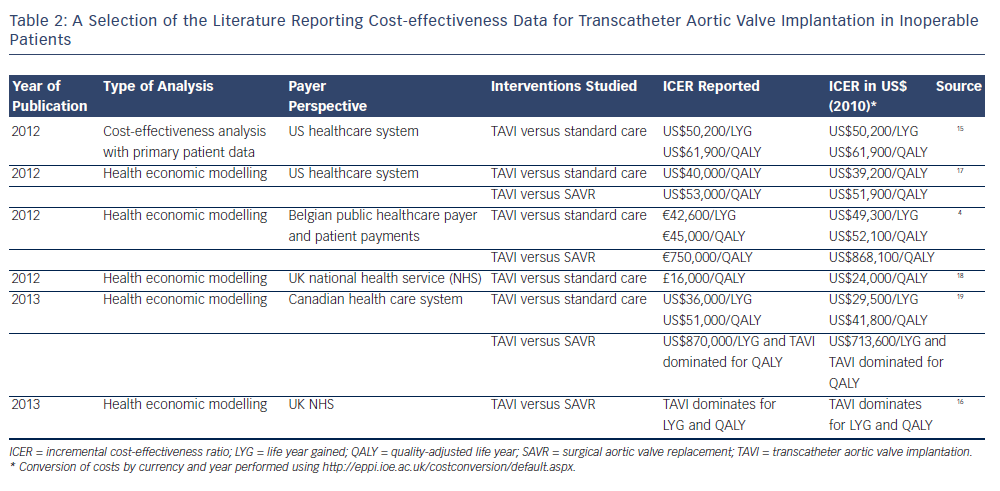

The only study designed to compare clinical and economic data between patients receiving TAVI, surgical replacement or standard medical care to date is the PARTNER trial, and cost-effectiveness results are only published on the cohort B, comparing TAVI with standard care in inoperable patients. Projecting costs and gains over a patient s lifetime, the authors reported an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for TAVI of US$50,200 per year of life gained or US$61,889 per QALY gained.15

Health Economic Modelling

When no primary, comparative patient data are collected, modelling  provides a way by which cost-effectiveness can be estimated for a given context (e.g. age groups or health systems). This is generally done by simulating the events (adverse events, death) occurring in a virtual cohort of patients, drawing on data from the literature (e.g. on survival probabilities, changes in quality of life after adverse events, etc.). The available studies using modelling techniques seem to converge at the conclusion that TAVI is favourable in inoperable patients when compared with standard medical care. However, when comparing TAVI and SAVR, results differ largely, for instance between a study in the National Health Service (NHS) context reporting TAVI to be dominant16 and a Belgian study finding an ICER of €750,000 (US$868,100) per QALY4 (see Table 2).

provides a way by which cost-effectiveness can be estimated for a given context (e.g. age groups or health systems). This is generally done by simulating the events (adverse events, death) occurring in a virtual cohort of patients, drawing on data from the literature (e.g. on survival probabilities, changes in quality of life after adverse events, etc.). The available studies using modelling techniques seem to converge at the conclusion that TAVI is favourable in inoperable patients when compared with standard medical care. However, when comparing TAVI and SAVR, results differ largely, for instance between a study in the National Health Service (NHS) context reporting TAVI to be dominant16 and a Belgian study finding an ICER of €750,000 (US$868,100) per QALY4 (see Table 2).

What Caveats Should be Kept in Mind?

The particularity of the current evidence on TAVI stems from the fact that almost every economic evaluation bases at least a part of its analyses on the sample of 358 patients in the PARTNER cohort B, of whom only 65 % consented to the collection of hospital billing data and all of whom (in the intervention group) received a valve from a single manufacturer.15 This seems to be a slim basis for drawing final conclusions on the cost-effectiveness of TAVI. In the following section, we will briefly review some further implications in terms of:

Firstly, most studies report on TAVI in a selective population of severely ill patients, either in the scope of the PARTNER trial or of registries. Yet, a main question for clinicians and payers is whether it may be worthwhile to extend the application of TAVI to less severe patients. Partly addressing this question, a recent study by Canadian colleagues reported an ICER of CA$51,000 (US$41,800) per QALY gained for inoperable patients (TAVI versus standard care) while TAVI (versus SAVR) was found to be dominated for operable patients.19 This implies that TAVI may be less cost-effective in patients in less severe condition. However, since no patient-based evaluation was explicitly designed to answer the question, the currently available evidence can only provide indications about the cost-effectiveness in a wider patient population. Secondly, differences in health system and population characteristics are often considerable and may for instance concern unit costs or the baseline prevalence and incidence of cardiovascular diseases. An illustration is the difference in TAVI procedure cost, which was reported to be US$1,530/hour in the PARTNER trial and only £524/ hour (US$785) in a UK analysis.15,18 Such variation may in part explain the differences in the reported ICER and are most likely rooted in distinct payment and organisational arrangements, besides potential differences in the calculation method. Therefore, the country in which a study has been conducted must always be considered when judging and comparing cost-effectiveness results.

Finally, the variation in results of the presented studies may in part be due to assumptions and methodological choices made in the process of health economic modelling. For instance, the study of Neyt and colleagues simulated the outcomes of their patient cohort (TAVI versus SAVR) over the period of only one year (based on the rationale that there was no significant survival difference in the PARTNER trial for these patients), leading to an ICER of €750,000/QALY (US$868,100).4 Conversely, Gada and colleagues modelled the outcomes in their analysis over the lifetime of the patients and found an ICER of US$53,000/QALY.17 Other choices to be made for such types of modelling analyses include what events will be considered in the follow-up (e.g. stroke, re-hospitalisations) and how quality of life will be taken into account. It is important to be aware that such assumptions always have to be made in modelling analyses, which is why it is worthwhile to carefully read the methods section of a publication before interpreting the results.