Defining ‘Acute Heart Hailure’ – A Spectrum of Clinical Syndromes

‘Acute heart failure’ has been criticised as an imprecise term that has consistently defied a consensus definition, wit h disparate interpretations across clinical medicine and the clinical trial environment.15 One recent definition is: “The rapid onset of a clinical syndrome where the heart is unable to pump adequate blood to provide for the needs of the body.”12 In UK clinical practice, the term is generally taken to describe the rapid onset of the symptoms and signs of HF occurring over hours to days; typically resulting in hospital admission. Conversely, AHF has also been used to in reference to any patient with HF requiring hospital admission. The latter term confusingly encompasses a different patient population by including those with a subacute or chronically progressive time course. Either may reflect a ‘decompensation’ of known HF, or a de novo presentation in a patient previously undiagnosed.

h disparate interpretations across clinical medicine and the clinical trial environment.15 One recent definition is: “The rapid onset of a clinical syndrome where the heart is unable to pump adequate blood to provide for the needs of the body.”12 In UK clinical practice, the term is generally taken to describe the rapid onset of the symptoms and signs of HF occurring over hours to days; typically resulting in hospital admission. Conversely, AHF has also been used to in reference to any patient with HF requiring hospital admission. The latter term confusingly encompasses a different patient population by including those with a subacute or chronically progressive time course. Either may reflect a ‘decompensation’ of known HF, or a de novo presentation in a patient previously undiagnosed.

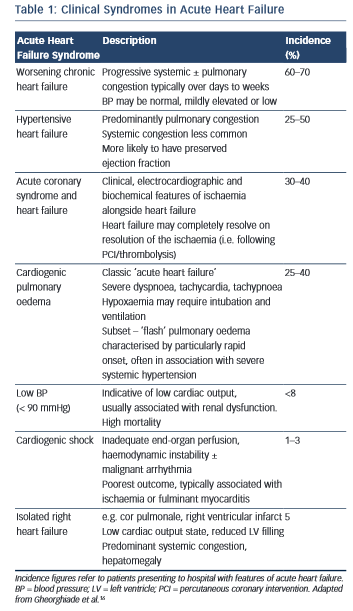

In reality, the clinical features of AHF result from a heterogeneous group of syndromes with significant overlap reflecting multiple underlying aetiologies, of which only around 50 % have a reduced left ventricular (LV) ejection fraction (EF) (see Table 1).16 The clinical severity may vary in accordance with the particular syndrome, (e.g. from predominant peripheral oedema to cardiogenic shock), or dependent on the individual patient; while certain presentations require specific treatments delivered in a time-critical manner (e.g. HF with an acute coronary syndrome). For optimal management, therefore, it is essential that the assessing clinician is able to elicit and interpret the clinical history and physical examination signs to highlight both the diagnosis, the likely underlying cause and potential precipitants.

Clinical Signs

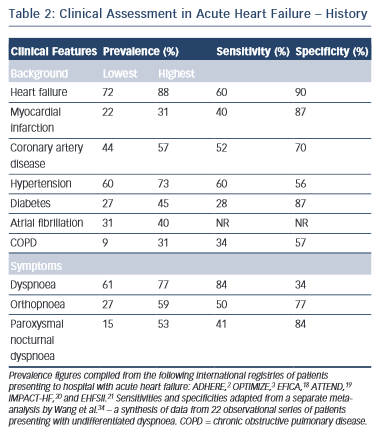

While the expected clinical features of a patient with AHF can be recounted by every competent medical student, their precise prevalence in clinical practice and relative discriminatory power in excluding other differential diagnoses have proven more difficult to quantitate formally. Clinical trials provide a wealth of high-volume information with accurate follow-up data, but limit their broader applicability by omitting a large proportion of ‘real world’ patients through strict inclusion criteria, typically excluding for example, the elderly and those with multiple co-morbidities.17 A number of large observational cohort studies have been undertaken over recent years in part to combat this shortcoming.2,3,18–21 The results are summarised in Table 2 and merit discussion below.

History

The background of patients presenting acutely with features of HF is largely consistent. They tend to be elderly, with a mean age of 60–65 in clinical trials, and 70–75 in observational series.2,3,18–23 Most registries identify a slight male preponderance (59–61%),18–21 although this is not always the case.2,3 In Western populations, most have a pre-existing history of HF (67–88 %).2,3,18,20,21 Other common co-morbidities include hypertension (60–73 %), diabetes mellitus (27–45 %), atrial fibrillation (31–40 %) and renal dysfunction (28–30 %).2,3,18–21 Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an important confounder in the differential diagnosis is also prevalent (9–31 %).2,3,18–21,24

Dyspnoea i s the most common presenting symptom and is the most sensitive, although not entirely ubiquitous (prevalence 61–95 %) indicator of congestion.2,3,6,18–21 It should be categorised in accordance with an accepted scale (e.g. New York Heart Association functional classification).25 This documentation is important for ongoing management as the severity of dyspnoea predicts mortality and is stubbornly resistant to symptomatic control in a significant proportion of patients despite optimal therapy.26 While the prevalence of dyspnoea in other pathologies (e.g. COPD) means that it lacks sufficient discriminatory power in isolation, it should always act as a flag to the presence of AHF within the differential diagnosis, ranking high up the list in those patients fitting the above demographic and co-morbid profile. Orthopnoea (27–59 %) and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea (15–53 %), the archetypal textbook symptoms of HF, typically reflect a more-severe presentation and are unsurprisingly less common but less ambiguous. However, they still lack the requisite specificity (77 and 84 %, respectively) for diagnosis when considered in isolation in patients presenting to the emergency department with undifferentiated dyspnoea (see Table 2).2,3,18–25

s the most common presenting symptom and is the most sensitive, although not entirely ubiquitous (prevalence 61–95 %) indicator of congestion.2,3,6,18–21 It should be categorised in accordance with an accepted scale (e.g. New York Heart Association functional classification).25 This documentation is important for ongoing management as the severity of dyspnoea predicts mortality and is stubbornly resistant to symptomatic control in a significant proportion of patients despite optimal therapy.26 While the prevalence of dyspnoea in other pathologies (e.g. COPD) means that it lacks sufficient discriminatory power in isolation, it should always act as a flag to the presence of AHF within the differential diagnosis, ranking high up the list in those patients fitting the above demographic and co-morbid profile. Orthopnoea (27–59 %) and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea (15–53 %), the archetypal textbook symptoms of HF, typically reflect a more-severe presentation and are unsurprisingly less common but less ambiguous. However, they still lack the requisite specificity (77 and 84 %, respectively) for diagnosis when considered in isolation in patients presenting to the emergency department with undifferentiated dyspnoea (see Table 2).2,3,18–25

Other important but non-specific symptoms of HF include fatigue, wheeze, abdominal bloating, anorexia, confusion and weight change; although their precise prevalence in patients presenting acutely is less well characterised in the literature.13 A cough productive of pink frothy sputum is relatively uncommon.

The precipitating factor behind the presentation may also be gleaned from the history and should be actively sought. One or more precipitants were identified in 61 % of 48,612 patents with known HF presenting acutely in the US. These included respiratory infection (15 %), ischaemia/acute coronary syndrome (15 %), arrhythmia (14 %), uncontrolled hypertension (11 %), medication non-adherence (9 %), worsening renal dysfunction (7 %), diet non-adherence (5 %) and others. Nineteen per cent of patients had more than one precipitant to be addressed.27 In a smaller cohort (n=150) concentrating specifically on acute pulmonary oedema, the identified precipitants were similar including hypertension (58 %), ischaemia (38 %), infection (37 %), arrhythmia (28 %) and anaemia (21 %) among others.28