Integrated Assessment – How to Improve Time to Diagnosis

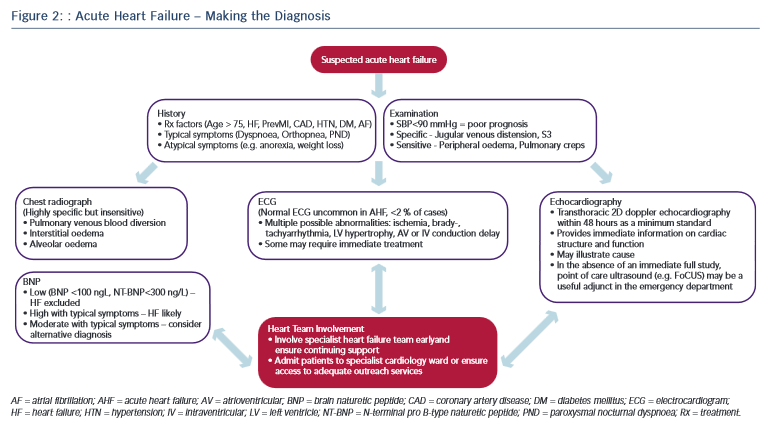

Recognising the diagnostic limitations of the clinical and simple radiographic parameters outlined above, contemporary practice guidelines emphasise the essential role of targeted investigations in identifying cardiac abnormalities to improve diagnostic accuracy.1 2–14 The pivotal role of the three most crucial investigations (ECG, echocardiography, biomarkers) is discussed below and illustrated in the diagnostic pathway of AHF (see Figure 2).

2–14 The pivotal role of the three most crucial investigations (ECG, echocardiography, biomarkers) is discussed below and illustrated in the diagnostic pathway of AHF (see Figure 2).

The ECG remains integral to the investigative armamentarium of the physician assessing a patient with suspected AHF, and may identify a host of abnormalities (e.g. brady- or tachyarrythmia, ischaemia, LV hypertrophy, atrioventricular or intraventricular conduction delay) to increase clinical suspicion and highlight precipitants that may require specific immediate management (reperfusion, pacing, rate control, anticoagulation, etc.) Indeed, an entirely normal ECG trace in AHF is highly unusual (<2 % of cases) yet not sufficient to independently rule out the diagnosis.58

Naturetic hormones are released by the heart in the presence of disease or in response to increased atrial or ventricular load. They lack the requisite specificity to diagnose HF in isolation, being secreted in other states such as arrhythmia, pulmonary embolism, renal failure, obesity and advancing age. However the sensitivity of the two most commonly used markers in clinical practice, brain naturetic peptide (BNP) and its precursor N-terminal pro B-type naturetic peptide (NT-proBNP), is such that a normal level (BNP <100 pg/L; NT-proBNP <300 pg/L) in the presence of suspected AHF effectively excludes the diagnosis.59 Moreover, a significant body of evidence highlights the magnitude of BNP/NT-proBNP elevation as an independent predictor of adverse outcome in AHF.60 Accordingly, obtaining BNP/NT-proBNP levels is now considered mandatory in suspected AHF.12 Furthermore, as familiarity with clinical use of biomarkers has increased, a pragmatism in their interpretation has continued to develop. For example, a patient with equivocal symptoms and signs and a modest elevation in BNP is liable to indicate HF; while severe symptoms combined with a mild elevation in BNP suggests an alternative diagnosis. Finally, recent work demonstrates that the use of multiple biomarkers in the elderly may augment diagnostic accuracy still further.61

Echocardiography provides immediate information on cardiac anatomy (chamber volumes and mass, valve structure) and function (ventricular wall motion, valvular function, pulmonary artery pressures) and plays an indispensable role in both the diagnosis of HF and guiding specialist management.13,14 The myriad potential echocardiographic abnormalities in AHF lie outside the scope of this article and have recently been discussed extensively elsewhere.62,64 Nevertheless it is important to emphasise that while the evidence base around the precise timing and modality of echocardiography in AHF requires further development, a transthoracic 2D doppler study within 48 hours is regarded as the minimum standard of care.12

Several pilot studies also highlight a potential emerging role for point of care ultrasonography in the emergency department as a supplementary tool to rapidly assess for filling status (e.g. inferior vena cava parameters) and features of congestion (e.g. sonographic B-lines) in the dyspnoeic patient.63,64 Moreover, once a diagnosis is reached further testing targeted at revealing the underlying aetiology (e.g. coronary angiography, myocardial perfusion scan, cardiac magnetic resonance) is usually required.

While none of the above tests demonstrate sufficient diagnostic accuracy to be a singular ‘gold standard’ in AHF, their prompt initiation alongside timely access to relevant specialist HF input are recognised as central priorities in improving the standard of AHF care.11 The most recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines emphasise the importance of the provision of a specialist HF team (HF specialist nurses, consultant cardiologists specialising in HF, etc.) based on a cardiology ward with dedicated outreach services for all patients with suspected AHF, highlighting the consistent improved outcomes in national data sets from this approach.1,12 The key to improving the time to diagnosis and subsequent outcomes in AHF therefore lies in maintaining a high index of suspicion allied with an awareness of the limitations of clinical assessment and recognition of the requirement for major investigations combined with the appropriate organisation to deliver these and involvement of appropriate HF specialists in a practical and efficient manner (see Figure 2).

Limitations

The majority of the studies quoted above are based upon observational data and should be interpreted within the following important limitations. First, patient registries, while providing a wealth of high-volume data encompassing ‘real-world’ patients with few exclusion criteria, are often based on convenience, rather than consecutive samples and may employ heterogenous diagnostic criteria, particularly in HF where there is no recognised standard, which in both cases can introduce selection bias. Second, utilising the primary discharge diagnosis in order to identify cases may introduce a proportion of patients presenting emergently with another condition who subsequently went on to develop AHF during their hospital stay or conversely exclude patients for which HF was only a co-morbid diagnosis (e.g. myocardial infarction complicated by HF). Finally, the retrospective review of medical records, even when conducted alongside standardised methods is dependent upon the quality and accuracy of the original data entered.