VAD Thrombosis

VAD thrombosis, one of the most devastating complications of MCS, is defined as the development of a blood clot within one component of the device, including the inflow cannula, outflow cannula, and the rotor despite anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy.42 Since 2011, for unknown reasons, there has been a reported abrupt increase in

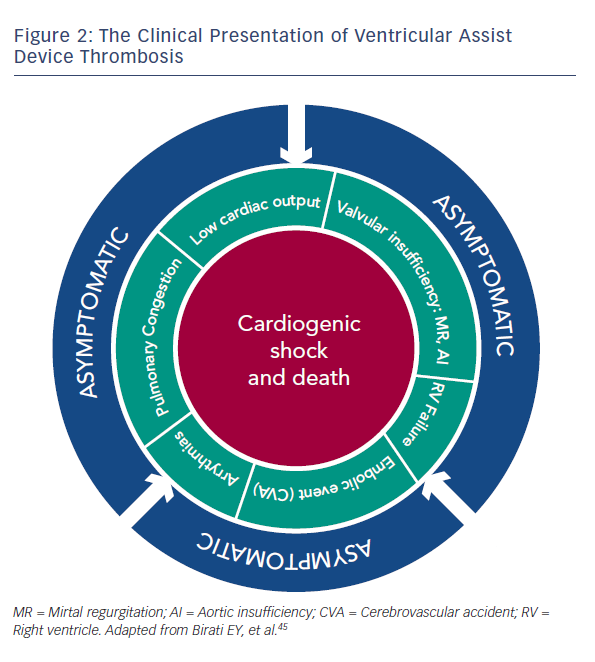

VAD thrombosis has more than one clinical presentation, and can involve a wide spectrum of clinical features, ranging from an asymptomatic patient to one with refractory cardiogenic shock and subsequent death.45 The various clinical presentations are detailed in Figure 2. Even early stages of VAD thrombosis may cause haemolysis that can be identified with elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, indirect bilirubin and plasma free haemoglobin (PFHg) levels.22 Uriel et al.46 reported that an LDH higher than five times normal was 100 % sensitive and 92 % specific for the diagnosis of pump thrombosis46, but our series argue that any value above the normal LDH range can imply VAD thrombosis.45

Patients with a suspected diagnosis of VAD thrombosis should be started on intravenous heparin, unless contraindicated; patients with highly suspected VAD thrombosis should be considered for pump exchange.47 Starling et al.42 showed that the six-month mortality of HeartMate II patients treated with device replacement was similar to the mortality of patients who did not have pump thrombosis.42 In patients with HeartWare HVAD thrombosis it is reasonable to start thrombolysis if the patient is haemodynamically stable and has no contraindications for thrombolytic therapy. However, if the HVAD patient does not improve clinically or suffer from haemodynamic instability, pump replacement should be considered.47

Acute Right Ventricular Failure

Acute RV failure is a frequent complication, occurring in 20–50 % of patients following LVAD implantation, and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.48–50 Acute RV failure post-LVAD implantation is defined as a need for inotropes longer than 14 days after LVAD implant or the need for temporary RVAD placement after LVAD surgery.48,51

After LVAD placement, there is an abrupt decrease in the left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), followed by a decrease in left pulmonary capillary wedge pressure. In most patients this, in turn, causes a decrease in the pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), thus decreasing the afterload of the right ventricle.52 However, some patients have a significant shift of the inter-ventricular septum towards the LV secondary to the decrease in the LVEDP and LV size and consequently an increase in RV preload. This shift of the septum adversely affects the function of the RV. High device speeds enhance this inter-ventricular septum shift, and can further deteriorate the RV function. Thus, it is highly recommended to conduct repeat echocardiographic studies during the first days after the implantation and to adjust the pump speed according to the septal movement and the ventricles size. RV failure can result in inadequate filling of the LV. Since the LVAD is preload dependent, patients with acute RV failure may present with cardiogenic shock.

Up to 15 % of patients with acute RV failure will require RVAD implantation.53 These patients suffer from severe RV failure leading to end organ dysfunction and cardiogenic shock refractory to inotropes.53

In an effort to prevent RV failure, some authors advocate for the routine use of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition, nitric oxide, or Epoprostenol Sodium (Flolan) therapy in every patient with pre-implant PVR above 3.11

Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Approximately one forth of VAD patients suffer from gastrointestinal bleeding (GI)54; half of the bleeding episodes originate from the upper GI tract. Although angiodysplastic lesions are the predominant cause of bleeding, stress and peptic ulcers are common in this patient population as well.54

The increased risk of bleeding is associated with several factors. First, similar to the Heyde syndrome of aortic stenosis, LVAD rotors generate high shearing forces leading to degradation of von Willebrand factor and acquired von Willebrand syndrome.55–57 Second, the continuous-flow devices generate low pulse pressures, which may cause GI hypoperfusion leading to formation of angiodysplastic lesions.58 In addition, most VAD patients are treated regularly with anticoagulation and antiplatelet regimens, which further increases the risk of bleeding.54 Figure 3 summarises the recommended treatment strategy of GI bleeding.59