Vascular Risk in Cognitive Diseases

In 2010, the joint report of the World Health Organisation and Alzheimer’s Disease International claimed that there were 35.6 million people with dementia in the world, and anticipated that the figure would almost triple by 2050 (115 million)1. Four years later, the projection was increased by 15 % (135 million people with dementia)2. Longer life expectancy has contributed to this epidemic growth, especially in the population aged 60 or over, and particularly in the over-80 age group. According to the World Health Organisation, in high-income countries, average life expectancy is 8.7 years for 80-year-old men and 11 years for 80-year-old women, (30 % more than three decades ago)3. The main reason for this occurrence is the continuing drop in mortality rate from heart and cerebrovascular diseases due to the technological advances of the past 50 years. Identification of vascular risk factors, new drugs that have been developed and new techniques, such as coronary artery bypass grafting, balloon angioplasty and stent implants, paradoxically seem to have contributed to the main risk factor for dementia in old age. Medicine has improved the prognosis of manifest vascular disease, and it has also prolonged life expectancy; however, heart and cerebrovascular diseases are still the main cause of death throughout the world (≈30 %)4.

The same vascular risk factors that affect cardiovascular health also compromise cerebrovascular health. Vascular brain injury and the resulting cellular damage (oxidative stress, swelling) appear to be the causes of the altered brain ageing process, leading to increased risk for stroke, cognitive decline, dementia, depression, and other neurological problems, such as gait disorders.

From this perspective, the prevalence of dementia will continue to increase as long as the scientific method is systematically focused on the treatment for the dementia syndrome and not on its prevention. The only way to reduce or eradicate its incidence is by implementation of preventative approaches. In accordance with the World Health Organisation definition, prevention covers measures which not only to prevent the occurrence of disease, but also arrest its progress and reduce its effects once established, thus, it is imperative to appraise population vulnerability; i.e. ascertain what it is we have to prevent.

Cardiovascular Health and Incidence of Dementia Decline

Despite the fact that dementia has reached epidemic levels due to the increasing number of people that are affected by it, recent publications have reported its incidence is actually declining. This trend may follow improvements in education quality and more effective control of vascular risk factors.

Both the Mayo Clinic Study (2005)5 and the Health and Retirement Study (2008)6 informed a 50 % drop in the prevalence of cognitive decline (from 5.7 % to 2.9 %) in a 17-year period, and a 29 % drop (from 12.2 % to 8.7 %) in a nine-year period. The retrospective interpretation of these results is that this decrease stems from a reduction of the stroke rate, improvements in health education and favourable changes in lifestyle (i.e. control of vascular risk factors).

Three European studies (Rotterdam Study, Cognitive Function and Ageing Study I-II and a study carried out in the Swedish population)7,8,9, with similar results, agree that the explanation may be better control of vascular disease and vascular risk factors.

The comparison of two sub-cohorts in the Rotterdam study (10 years apart) underscored the finding that in the most recent cohort, the incidence of dementia was lower, the participants’ brains were bigger (i.e. less atrophy) with fewer white matter lesions7 , and this was attributed to the fact that this group took more anti- hypertensive and antithrombotic (aspirin) drugs and statins.

In a nutshell, “…there is evidence from various studies that in high- income countries, the incidence of dementia is decreasing due to high levels of education and improvement in cardiovascular health.” (Alzheimer’s Report 2014)2.

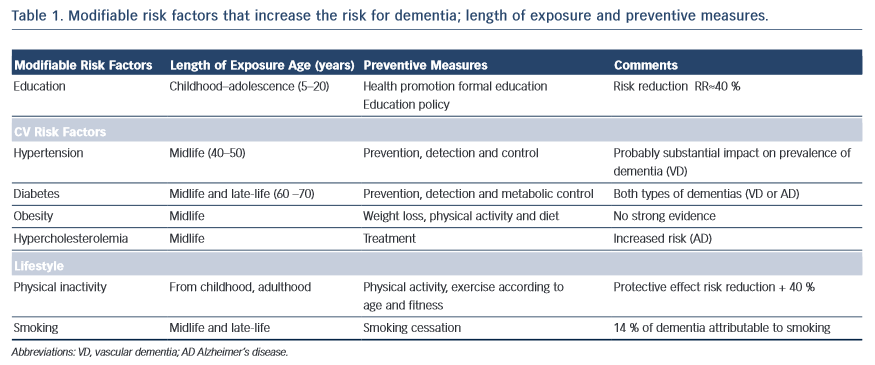

In essence, every case of vascular disease will be somehow associated with vascular brain injury and, consequently, with neurocognitive diseases. Middle-age hypertension is related to the progression of white matter lesions, cognitive impairment and mood disorders10,11, diabetes seems to add loss of brain volume to vascular lesions, and obesity has also been associated with higher risk for dementia13. Cognitive impairment in patients with metabolic syndrome appears to be directly linked to the number of components encompassed in the particular syndrome and the metabolic disorder involved14; smoking more than two packs of cigarettes a day increases the risk for dementia 20 years later15, and atrial fibrillation with inadequate anticoagulation therapy increases the risk for stroke and dementia (Alzheimer’s disease) irrespective of vascular disease16,17 (see Table 1).

New studies have reported that aggregate exposure to vascular risk factors since early stages in life is also associated with worsening cognition in mid-life18. Accordingly, identification of vascular risk factors and the duration of exposure when they may have had a negative impact on health can be considered targets for prevention.