Vascular Prevention of Cognitive Diseases

For more than two decades, vascular disease has been gaining ground within neurodegenerative diseases, among which dementias have a significant place. Risk factors that impair vascular health – hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and diabetes – contribute to hastening and compounding dementia and worsen its prognosis.

Considering the above hypotheses and published research devoted to investigating the link between vascular disease, cognitive decline and dementia, we can conclude that: i) patients with hypertension, whether isolated or associated with other vascular risk factors, present vascular brain injury and greater risk for dementia than the vascular disease- free population; ii) cases of Alzheimer’s disease are paradoxically more frequent than cases of vascular dementia among patients with vascular risk factors and vascular disease; iii) the association of vascular brain injury and brain neurodegenerative disorder is clinically expressed by greater cognitive decline; and iv) some studies have proved that the preservation and enhancement of vascular health through rigorous control of risk factors may prevent or delay the onset of dementia, and in those already diagnosed, may contribute to slowing of cognitive decline. Therefore, the promotion of vascular health becomes the focal point of primary and secondary prevention of dementias34.

Today we can conclude that vascular risk factors are shared by heart and brain. As a result, if we deem the seventh decade of life as the average age in which late-onset Alzheimer’s disease begins, our preventive attitude should target vascular risk factors 20 years earlier, that is, the mean age in which these factors’ presence becomes relevant. Furthermore, a recent publication points out that more than 30 % of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease cases may be attributed to the combination of vascular risk factors35.

Thus, if timely intervention manages to increase the control of vascular risk factors in the vulnerable population by 10 %, the projected effect would be a reduction in the number of cases of Alzheimer’s disease by one million, and by three million if c ontrol reaches 25 %. In other words, if we could delay onset of Alzheimer’s disease by five years, cases of dementia would be reduced by half within 10 years36.

ontrol reaches 25 %. In other words, if we could delay onset of Alzheimer’s disease by five years, cases of dementia would be reduced by half within 10 years36.

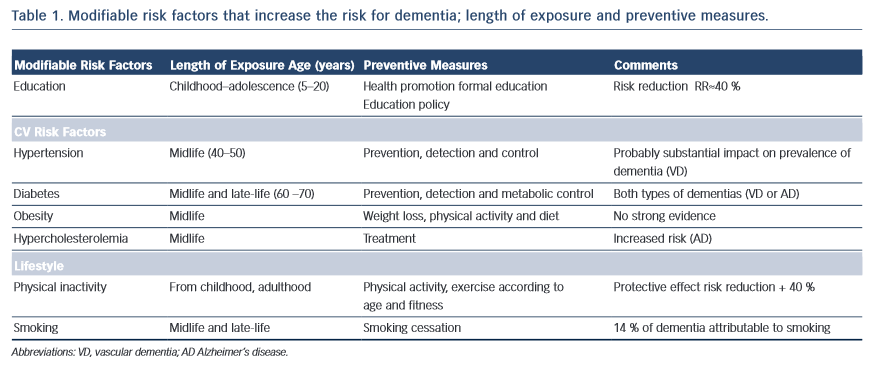

In 2011, the Alzheimer’s Disease International World Report recommended antihypertensive drugs, statins and physical activity among the most beneficial interventions for dementia prevention. All of these measures are aimed at preserving vascular health37, and do not exclude the need to recognise, reduce and treat vascular risk factors or cardiovascular disease in patients with dementia (see Table 1).

Prevention should include health promotion to inspire a change in the population towards healthier lifestyles and behaviours, while also raising awareness among physicians about these factors. In this way, the epidemic levels of dementia currently seen will be effectively managed by a population controlling its own health and through the identification of vulnerable individuals by the healthcare sector.

Some of the variables that operate in the clinical expression of dementia escape intervention (e.g. genetics, age), while others are modifiable. However, vascular risk factors that impact negatively on vascular health can be controlled. We cannot limit our efforts and simply wait until a drug treatment that can cure Alzheimer’s disease makes its appearance on the market (although that drug is necessary). Instead, our purpose should be to highlight prevention and promote vascular health as the only effective method for reducing the prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease.