Renal sympathetic denervation (RDN) has been introduced as a novel approach to treat patients with so-called resistant hypertension.1–3 The first randomised clinical trial showed an impressive 32/12 mmHg fall in blood pressure after six months in the intervention group (n=52) compared to the control group (n=54). However, with the recent publication of the Symplicity HTN-3 study in the US4 the world has become in doubt whether RDN lowers blood pressure. An editor of distinguished journal5 published his reflections and stated that the Symplicity HTN-3 results came as a shock to the world; a single but large and properly designed prospective randomised clinical trial could on its own neutralise hundreds of mostly observational studies, case reports and other enthusiastic publications emphasising the amazing effect of RDN, not only in patients with resistant hypertension, but also in a host of other diseases and conditions.

The initial enthusiasm followed by the setback of RDN can probably be summarised by a handful of explanations: 1) The role of the sympathetic system in the pathophysiology of hypertension is substantiated by a wealth of experimental and clinical arguments.6–12 On this background, enthusiasm surged when an intervention in this system seemed to drastically lower blood pressure; 2) Market-driven industry took control and exerted unprecedented influence on the medical community; 3) Subsequently, pitfalls in apparent treatmentresistant hypertensive patients, which are simple but well-known for decades, were suddenly forgotten including well described phenomena such as the placebo effect, regression to the mean, poor drug adherence13–15 and the Hawthorne effect.

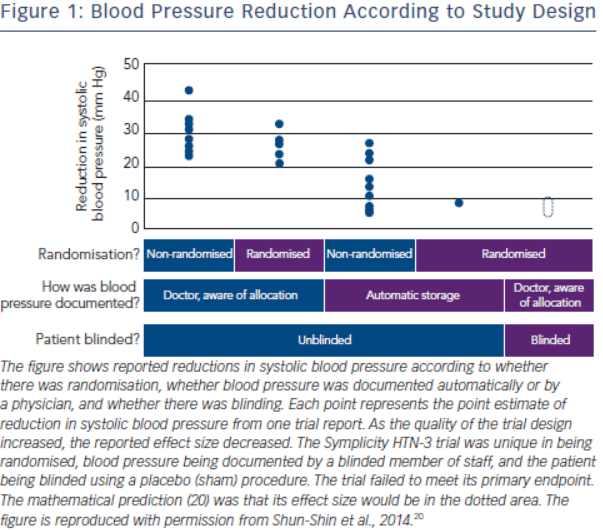

The history of the rise and decline of RDN deserves a more in-depth analysis. The first and for long the only prospective randomised clinical trial in this field, the Symplicity HTN-2 study2, was monitored by Ardian (Medtronic) who collected and processed the data.2 Usually, when such a task is given to industry, all measures are taken to secure confidence and trials are prospective, randomised and double-blinded.16–19 However, in this case, everything was open, making the trial particularly vulnerable to patients, physicians and sponsor-related biases.19 As indicated by Shun-Shin et al. in a recent editorial,20 “measurement of a noisy variable by unblinded optimistic staff is a known recipe for calamitous exaggeration”. This is illustrated in Figure 1. It is unfortunate that selection of patients enrolled in Symplicity HTN-2 and evaluation of efficacy were based on office rather than ambulatory blood pressure (ABPM), which is state-ofthe art,21 particularly in resistant hypertension.22 ABPM reduces observer bias and measurement error, minimises the white-coat effect and has greater reproducibility, and therefore provides a better estimate of a patient’s usual blood pressure and cardiovascular prognosis.23,24 Notwithstanding the well-known, major contribution of poor drug adherence to apparently resistant hypertension13–15,25–27, drug adherence was not monitored, either at baseline or during follow-up. This made the study vulnerable to the Hawthorne effect, i.e. patients changing behaviour – in this case starting taking their drugs as prescribed – in response to the intervention and massive attention devoted to them. The lack of blood pressure decrease in the control group also raised concerns. One would indeed suspect that patients in the control group had not taken their medications properly, in order to keep their blood pressure at a higher level that made them eligible for cross-over to RDN group.28,29 Finally, placebo effect and regression to the mean must also be taken into account. Noteworthy, the placebo effect is small by using ambulatory blood pressures21,30; however ambulatory blood pressures remain as sensitive to the Hawthorne effect as office blood pressure.

Despite the major limitations and potential biases of Symplicity HTN-2, a small open study with suboptimal design including only 106 patients followed up for six months, RDN was adopted in hundreds of centres worldwide. Medtronic Inc® (Minneapolis, Minnesota) paid $800 million to purchase Ardian® (Mountain View, California), the company that had developed the technology5, and more than ten companies developed their own RDN systems, five of which obtained the CE mark. The procedure was quickly reimbursed in Germany, and later on in Switzerland, Sweden and the Netherlands. While RDN remained an investigational procedure in the US, at least 8,00031, possibly 15,000 to 20,000 procedures were performed in Europe and in the rest of the world in less than four years, most of them using the Ardian-Medtronic® catheter. It may be hypothesised that the massive incomes generated by selling the Symplicity catheter to enthusiastic Europeans contributed to the expenses of the Symplicity HTN-3 study4, required by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before approval of RDN in the US.