Epidemiology

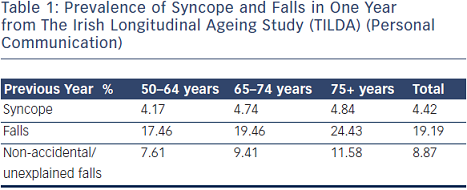

The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA [www.tilda.ie]) is a population-based study of adults 50 years and over  that incorporated questions on syncope and falls in addition to a broad spectrum of health, social and economic questions. A number of community dwelling adults (8,163), mean age 62, range 50–106 years, were asked whether they experienced fainting in their youth, throughout their life or over the past 12 months. A total of 23.6 % had one or more episodes in the previous 12 months of which 4.4 % were syncope and 19.2 % were falls (see Table 1). Although the prevalence of syncope rose with age, the increase in falls was much more remarkable, in particular the increase in non-accidental or unexplained falls was most striking. Unwitnessed syncope most commonly presents as non-accidental or unexplained falls, supporting the rising prevalence of atypical syncope with advancing years.

that incorporated questions on syncope and falls in addition to a broad spectrum of health, social and economic questions. A number of community dwelling adults (8,163), mean age 62, range 50–106 years, were asked whether they experienced fainting in their youth, throughout their life or over the past 12 months. A total of 23.6 % had one or more episodes in the previous 12 months of which 4.4 % were syncope and 19.2 % were falls (see Table 1). Although the prevalence of syncope rose with age, the increase in falls was much more remarkable, in particular the increase in non-accidental or unexplained falls was most striking. Unwitnessed syncope most commonly presents as non-accidental or unexplained falls, supporting the rising prevalence of atypical syncope with advancing years.

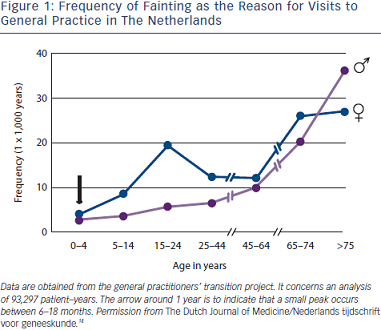

The General Practitioners’ Transition Project in the Netherlands demonstrated that the age distribution of patients presenting to their GP with syncope shows a peak in females at 15 years of age and a second peak in older patients (see Figure 1).14 The Framingham Offspring study similarly demonstrates a bimodal peak of first syncope  in mid-teens and over 70 years.15

in mid-teens and over 70 years.15

The true prevalence of syncope is underestimated due to the phenomenon of amnesia for T-LOC. Amnesia has been reported in patients with vasovagal syncope (VVS) and carotid sinus syndrome (CSS),3,16 but is likely to be present in all causes of syncope. The overlap between syncope and falls also leads to under-reporting.6

Causes of Syncope in the Elderly

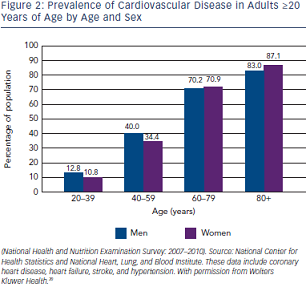

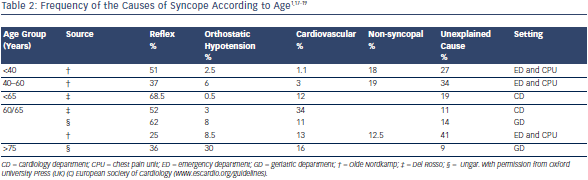

Reflex syncope and orthostatic hypotension (OH) are the most frequent causes of syncope in all age groups and clinical settings, and responsible for the majority of episodes in younger patients. However, cardiac causes of syncope, structural and arrhythmic, become more common in older patients and are responsible for one-third of syncope in patients attending the Emergency Room and Chest Pain Unit1,17–19 (see Table 2,17–19

Figure 2 20 and Figure 3.21)

The prevalence of unexplained syncope varies according to diagnostic facilities and age from 9 to 41 % (see Table 2 1,17–19). In the older patient, history may be less reliable and multiple causes of syncope may also be present (see Table 3).4,18,22–24 Multi-morbidity and polypharmacy are more common in older patients with syncope and can add to the complexity of identifying an attributable cause of events.25

Approach to the Older Person Presenting with Syncope

Classification

Syncope is classified as reflex/neurally mediated syncope, syncope secondary to OH and cardiac syncope.1

Assessment

Initial Evaluation

Initial evaluation should establish whether T-LOC occurred, whether aetiology has been identified and whether there is any evidence of a high risk of cardiovascular events or death.1,21 The initial evaluation in patients over 50 years includes detailed history, collateral history, driving history, physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), measure of orthostatic BP, routine blood tests and CSM. Where possible, the history should elicit ‘the 3 Ps’ (provokers, prodrome, posture), as well as circumstances leading to the event, description of the event, duration of the event, details of the recovery phase and a thorough medication history,1 coupled with a witness account. History alone cannot be relied upon in the older population as commonly these patients (28 % in one study3) experience amnesia for loss of consciousness.3,18 In 50 % of cases of syncope in the older population an accurate collateral history is not available.6 The differential diagnosis of syncope most frequently includes epilepsy, strokes and transient ischaemic episodes and falls (see Table 4).1 The absence of T-LOC is important in differentiating between syncope and ‘drop attacks’, which are defined as a loss of postural control when the patient falls without loss of consciousness but with difficulty in resuming the erect position after the event.26

history should elicit ‘the 3 Ps’ (provokers, prodrome, posture), as well as circumstances leading to the event, description of the event, duration of the event, details of the recovery phase and a thorough medication history,1 coupled with a witness account. History alone cannot be relied upon in the older population as commonly these patients (28 % in one study3) experience amnesia for loss of consciousness.3,18 In 50 % of cases of syncope in the older population an accurate collateral history is not available.6 The differential diagnosis of syncope most frequently includes epilepsy, strokes and transient ischaemic episodes and falls (see Table 4).1 The absence of T-LOC is important in differentiating between syncope and ‘drop attacks’, which are defined as a loss of postural control when the patient falls without loss of consciousness but with difficulty in resuming the erect position after the event.26

If syncope remains undiagnosed, further investigation is necessary, including in head-up tilt (HUT), cardiac investigations and ambulatory BP monitoring.24,27 In some studies up to 30 % of older patients with syncope have more than one possible attributable cause, emphasising the necessity for a full comprehensive assessment in the older patient.22,28