Introduction

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) has enhanced our understanding of atherosclerotic plaque morphology, and provides a unique opportunity to guide cardiovascular interventions and evaluate the results of these interventions. IVUS is safe, cost efficient and effective in guiding clin ical decisions and cardiovascular interventions and improves outcomes when used during coronary artery stenting. Although a comprehensive IVUS overview is beyond the scope of this article, this review will focus on the impact of IVUS in clinical practice.

ical decisions and cardiovascular interventions and improves outcomes when used during coronary artery stenting. Although a comprehensive IVUS overview is beyond the scope of this article, this review will focus on the impact of IVUS in clinical practice.

Intravascular Ultrasound Transducer Types and Common Artifacts

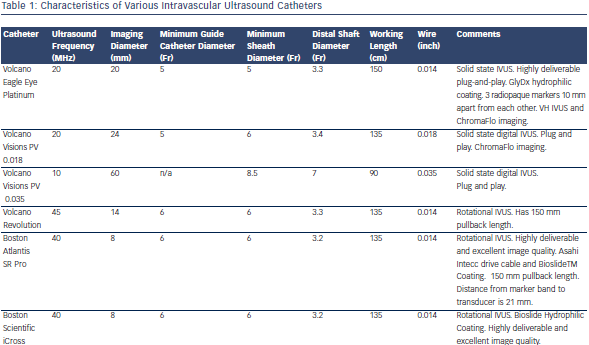

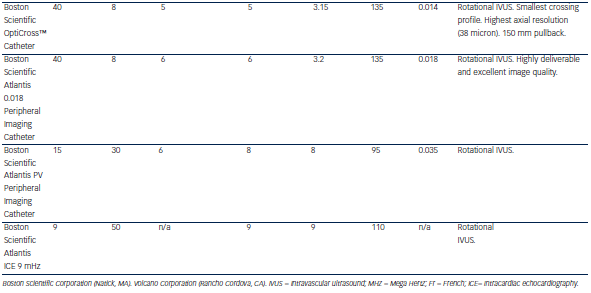

Table 1 describes characteristics of some IVUS catheters. There are two different catheter types – mechanical-state or rotating transducer catheters, and solid-state or electronic array catheters. Most Volcano Corporation (Rancho Cordova, CA) catheters use electronic array technology, where multiple phased-array elements are oriented circumferentially and receive backscattered ultrasound signals which are then processed into real-time images. These catheters do not require rotation for image acquisition. Boston Scientific Corporation (Natick, MA) catheters, and catheters such as the ViewIT, Terumo Corporation (Tokyo, Japan), and HD-IVUS, Acist Medical Systems Inc. (Eden Prairie, MN), use a rotating transducer design where one rotating element captures signals with each revolution. This  design requires a catheter housing and a flexible cable to rotate the transducer element. Frequent system flushing is imperative to eliminate air bubbles that may accumulate within the catheter housing creating image artifacts. A wire channel runs adjacent to the Boston Scientific transducers and may also create artifacts. Volcano catheters eliminate the wire artifact by housing the guide wire central to its transducer elements. Non-uniform rotational distortion (NURD) may occur during non-homogeneous transducer rotation seen in electronic array catheters, frequently due to wire bias in the presence of vessel tortuosity. Boston Scientific offers an automatic software correction to minimise NURD. Figure 1 shows various image artifacts.

design requires a catheter housing and a flexible cable to rotate the transducer element. Frequent system flushing is imperative to eliminate air bubbles that may accumulate within the catheter housing creating image artifacts. A wire channel runs adjacent to the Boston Scientific transducers and may also create artifacts. Volcano catheters eliminate the wire artifact by housing the guide wire central to its transducer elements. Non-uniform rotational distortion (NURD) may occur during non-homogeneous transducer rotation seen in electronic array catheters, frequently due to wire bias in the presence of vessel tortuosity. Boston Scientific offers an automatic software correction to minimise NURD. Figure 1 shows various image artifacts.

Available IVUS cathete rs used for most coronary, renal, iliac and infrainguinal arterial assessment are compatible with 5–6 French sheaths. Low frequency catheters offer an expanded imaging field at the expense of proximal image resolution and are utilised for aortic and venous imaging. High-frequency catheters offer improved image resolution but have a narrower field of imaging. The axial resolution varies among common imaging catheters: Eagle Eye® – <170 microns; Revolution™ – 50 microns; iCross™ – 43 microns and OptiCross™ – 38 microns.

rs used for most coronary, renal, iliac and infrainguinal arterial assessment are compatible with 5–6 French sheaths. Low frequency catheters offer an expanded imaging field at the expense of proximal image resolution and are utilised for aortic and venous imaging. High-frequency catheters offer improved image resolution but have a narrower field of imaging. The axial resolution varies among common imaging catheters: Eagle Eye® – <170 microns; Revolution™ – 50 microns; iCross™ – 43 microns and OptiCross™ – 38 microns.

Near-field artifacts include ringdown and blood speckle artifacts, with the latter one clearing during saline flushing. With phased array catheters, interference can occur around the catheter creating a resonance phenomenon that leads to a long and uninterrupted echo producing a blind area or ringdown artifact.

Side lobe artifacts are caused by multiple low-energy sound beams that arise from the main ultrasound beam. The receiver detects and erroneously assigns these low energy beams to the main beam parallel to the false location. They are commonly bright rounded lines displayed over hypoechoic or anechoic structures adjacent to hyperechoic structures.

Vessel measurements are ideally performed with the transducer perpendicular to the vessel wall. Position artifacts caused by catheter obliquity, and vessel curvature or eccentricity may especially be of clinical significance in larger vessels. Catheter motion artifact may result from forward transducer translation during vessel flushing. Axial translation may also be observed during cardiac or breathing cycle variation.