IVUS for BMS and DES Implantation

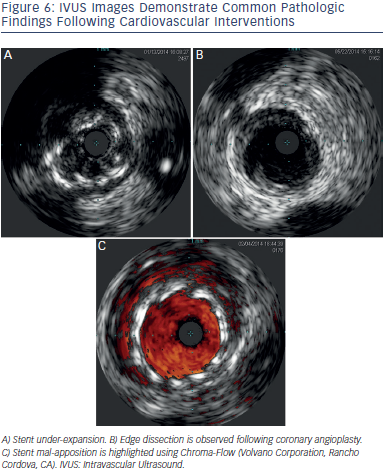

Pre-intervention vessel size, lesion length and morphology are evaluated to select the appropriate strategy and stent size and length. Post-intervention stent landing, expansion and apposition are evaluated. Complications are excluded (e.g. malapposed or under-expanded stents, geo graphic miss, dissections, plaque prolapse, residual thrombus), and fine tuning performed. Figure 6 demonstrates some post intervention issues encountered during IVUS.

graphic miss, dissections, plaque prolapse, residual thrombus), and fine tuning performed. Figure 6 demonstrates some post intervention issues encountered during IVUS.

Fluoroscopy may miss stent under-expansion, a predictor of stent thrombosis (ST) after bare metal stent (BMS) implantation.15 Fujii et al.16 identified stent under-expansion and residual reference segment stenosis as predictors of ST after sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) implantation. In addition to stent under-expansion, a higher residual disease burden at the stent edges has been associated with stent thrombosis.26 This may explain the higher rate of mIss noted by Costa et al.27 in a cohort of patients with geographic miss following SES implantation.

Higher BMS ISR rates are observed with smaller minimal stent area (MSA) and longer stent length.28 A stent minimal luminal area (MLA) < 6 mm2 was observed in 28 % of BMS ISR cases. Similarly 4.5 % of these ISR cases had unrecognised mechanical complications (geographic miss, stent deformation and balloon stripping during the implantation procedure) readily detectable by IVUS.29 Everolimus eluting stents (EES) associated mechanical complications, (e.g. partial or complete stent fracture, strut fracture with overlapping stent fragments, and longitudinal deformation) have been associated with excessive neo-intimal hyperplasia, ISR and repeat revascularisation.30 Sonoda et al.31 observed a correlation between BMS and SES MSA and long term development of ISR. Fujii et al.32 found stent under expansion (MSA < 5.0 mm2) to be associated with ISR after SES implantation. Similarly, Hong et al.33 corroborated MSA < 5.5 mm2 as an independent predictor of angiographic restenosis after SES implantation and also found a stent length > 40 mm2 to predict restenosis. A meta-analysis34 evaluating BMS and Taxus paclitaxel eluting stent (PES), observed that IVUS maximum percentage of intimal hyperplasia correlated with restenosis at nine months.

Sakurai et al.35 found that residual reference vessel plaque burden and stent over-sizing relative to the reference vessel were associated with edge stenosis in a SES when compared to a BMS cohort. Liu et al.36 found residual edge plaque burden and not edge lumen area to be predictive of nine month stent edge restenosis after BMS or TAXUS PES implantation. Costa et al.27 found a high rate (66.5 %) of longitudinal and axial geographic miss following SES implantation. At one year follow-up TVR rates in the geographic miss group was 5.1 % compared to 2.5 % in the non-geographic miss group (p=0.025). There was a 3-fold increase in MI rates associated with geographic miss (2.4 % vs 0.8 %; p=0.04). The long-term health outcome and mortality evaluation after invasive coronary treatment using drugeluting stents with or without the IVUS guidance study11 failed to demonstrate superiority of IVUS use to guide DES implantation using standard high pressure post-dilatation. However, the Angiography vs IVUS Optimisation (AVIO) study12 showed benefit in the postprocedure minimal lumen diameter (2.70 mm +/- 0.46 mm vs 2.51 +/- 0.46 mm; P = .0002), when using IVUS compared to angiography to optimise implantation. At 24-months follow-up no differences were observed for cumulative MACE, cardiac death, MI, target lesion revascularisation or target vessel revascularisation. The Assessment of dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES),37 a prospective, multicentre, non-randomised study of 8,583 consecutive patients, showed that IVUS guidance was associated with a reduction in stent thrombosis (0.6 % vs 1.0 %; HR 0.40; 95 % CI 0.21–0.73; P=0.003), MI (2.5 % vs. 3.7 % HR 0.66; 95 % CI 0.49–0.88; P=0.004), and major adverse cardiac events (cardiac death, MI, or stent thrombosis), (3.1 % vs 4.7 %; HR 0.70; 95 % CI 0.55-0.88; P=0.002) within one year after DES implantation. Larger stents, longer stents and/or higher inflation pressures were used in 74 % of IVUS guided cases. A pooled analysis of four registries included 1,670 patients with LM disease undergoing DES implantation. Thirty percent of the group underwent IVUS guided DES implantation and were compared against the non- IVUS group using a propensity score-matching method. Survival free of cardiac death, MI and TLR at three years was significantly lower in the IVUS guided group (88.7 % vs 83.6 %, p: 0.04). Similarly thrombosis was lower in the IVUS guided group (0.6 % vs. 2.2 %, p = 0.04).38 Two recent metaanalyses favour the use of an IVUS guided strategy as opposed to an angiography guided strategy for DES implantation. One meta-analysis included 26,503 patients from three randomised and 14 observational studies. IVUS-guided PCI was associated with larger, longer and more stents, and lower risk of death (OR 0.61, 95 % CI 0.48 to 0.79, p<0.001), MI (OR 0.57, 95 % CI 0.44 to 0.75, p<0.001), TLR (OR 0.81, 95 % CI 0.66 to 1.00, p=0.046), and stent thrombosis (OR 0.59, 95 % CI 0.47 to 0.75, p<0.001) after drug-eluting stent implantation.39 These results were consistent with a meta-analysis by Jang et al.40 which encompassed 11,793 IVUS guided and 13,056 angiography guided patients from three randomised trials and 12 observational studies. In this study, the IVUS guided strategy was associated with lower rates of MACE (OR 0.79, 95 % CI 0.69 – 0.91, p: 0.001), all - cause mortality (OR 0.64, 95 % CI 0.51 – 0.81, p: 0.001), MI (OR 0.57, 95 % CI 0.42 – 0.78, p: < 0.001), TVR (OR 0.81, 95 % CI 0.68–0.95, p: 0.01) and stent thrombosis (OR 0.59, 95 % CI 0.42–0.82, p = 0.002).

CI 0.44 to 0.75, p<0.001), TLR (OR 0.81, 95 % CI 0.66 to 1.00, p=0.046), and stent thrombosis (OR 0.59, 95 % CI 0.47 to 0.75, p<0.001) after drug-eluting stent implantation.39 These results were consistent with a meta-analysis by Jang et al.40 which encompassed 11,793 IVUS guided and 13,056 angiography guided patients from three randomised trials and 12 observational studies. In this study, the IVUS guided strategy was associated with lower rates of MACE (OR 0.79, 95 % CI 0.69 – 0.91, p: 0.001), all - cause mortality (OR 0.64, 95 % CI 0.51 – 0.81, p: 0.001), MI (OR 0.57, 95 % CI 0.42 – 0.78, p: < 0.001), TVR (OR 0.81, 95 % CI 0.68–0.95, p: 0.01) and stent thrombosis (OR 0.59, 95 % CI 0.42–0.82, p = 0.002).

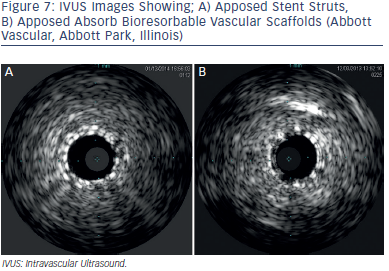

The achievement of optimal stent size cannot be predicted using the manufacturer’s compliance charts when using BMS or DES. The average achieved minimal stent diameter (MSD) is 75 % of the predicted MSD and 66 % of the predicted MSA when compared to IVUS measurements.41 Adequate vessel sizing is especially important when using bioresorbable vascular scaffolds.42 Scaffolds require quantitative coronary angiography or IVUS guided measurement for optimal results. An IVUS example of scaffolds as compared to stent struts is shown on Figure 7.