Nurture – How is Exercise Associated with Disease Onset and Clinical Course?

Influence of Exercise on Disease Expression

The appreciation of the association of exercise and ARVD/C began with the twin observations that ARVD/C patients were frequently athletes and that arrhythmias occurred disproportionately during athletic activity in ARVD/C patients.13,15 A review of autopsies in the Veneto region of Italy showed participation in competitive athletics resulted in a more than fivefold increase in sudden cardiac death risk among young patients with ARVD/C.14 Consistent with this observation, implementation of a pre-participation screening programme resulted in a sharp decline in such deaths.49 Th e first observation that athletic involvement correlated with disease characteristics among living patients was by Sen-Chowdhry and colleagues who found that among a group of 116 ARVD/C patients, the 11 patients who participated in long-term endurance training had more severe RV dysfunction.45

e first observation that athletic involvement correlated with disease characteristics among living patients was by Sen-Chowdhry and colleagues who found that among a group of 116 ARVD/C patients, the 11 patients who participated in long-term endurance training had more severe RV dysfunction.45

During the past 2 years, research has accelerated with four clinical studies focused on addressing the extent to which exercise influences ARVD/C onset and disease course. These studies, reviewed below, make a compelling case that there is a dose-dependent relationship between exercise intensity and duration and disease severity.

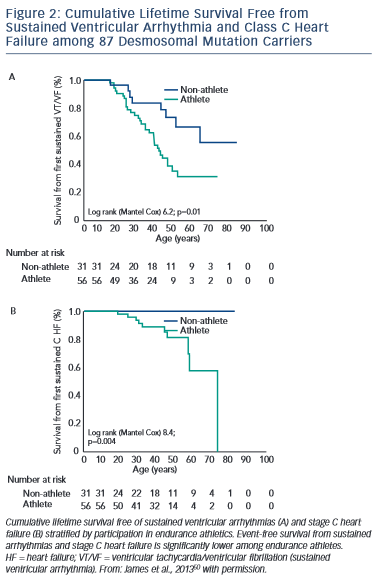

The first study, published by James et al.,50 collected exercise history by interview from 87 carriers of heterozygous desmosomal mutations ascertained from the Johns Hopkins ARVD/C Registry. Endurance athletes were defined as participants in a sport with a high dynamic demand (>70 % Max O2), based on the 36th Bethesda Conference Classification of Sports (Task Force 8),51 for at least 50 hours/year at vigorous intensity. The results of the study showed that both participation in vigorous endurance (aerobic) athletics and greater duration of annual exercise were associated with an increased likelihood of ARVD/C diagnosis in a dose-dependent fashion. Similarly, as shown in Figure 2, survival from first sustained ventricular arrhythmia and onset of Class C heart failure was worse among athletes. Furthermore, the study suggested that modifications in exercise following clinical presentation could alter clinical course. Mutation carriers who continued to participate in high duration exercise after clinical presentation had worse survival from first ventricular arrhythmia compared with individuals who reduced their exercise. Taken together these data suggested an important link between exercise and the outcomes of desmosomal mutation positive ARVD/C patients and family members.

These findings were subsequently confirmed in both European and multicentre North American populations and in ARVD/C patients without desmosomal mutations. Saberniak and colleagues investigated the impact of exercise on myocardial function among 110 Scandinavian ARVD/C patients (both with and without desmosomal mutations) and mutation carrier family members.22 Data were again collected by interview. Exercise participation was measured by metabolic equivalent (MET)-minutes per week with patients participating in vigorous (≥6 METs) physical activity for ≥4 hours/week classified as athletes. The authors showed that athletes were more likely to meet diagnostic criteria, experience ventricular arrhythmias and progress to cardiac transplant. Furthermore, they found that both RV and LV function were significantly reduced in athletes and that intensity of exercise was correlated with the extent of structural dysfunction in a dose-dependent fashion.

Next, the Johns Hopkins group confirmed the association of exercise with clinical course among 43 ARVD/C index patients without desmosomal, PLN or TMEM43 mutations. Patients were categorised as athletes using the same criteria previously described. Sawant et al.52 found that those participating in the highest intensity (MET-hours/ year) exercise prior to clinical presentation had earlier onset, worse RV structural abnormalities and poorer survival from ventricular arrhythmias in follow-up.

Finally, Ruwald et al. recently reported data from 108 probands ascertained in the North American ARVC registry.53 For this study patients self-reported whether they were inactive, recreational athletes or competitive athletes both prior to diagnosis and in follow-up. Similar to the findings of James et al., Sawant et al. and Saberniak et al., competitive athletes had a worse clinical profile with earlier symptom onset, and a worse survival from a combined ventricular tachyarrhythmia/death endpoint. They also noted that individuals who continued competitive exercise had a significantly worse arrhythmic course following diagnosis compared with those who reduced exercise, validating the initial findings of James et al.50 By contrast, the authors detected no differences in age of onset or risk of ventricular arrhythmias/death between patients who rated themselves as inactive versus recreational athletes. While these data are somewhat reassuring, some caution is warranted as close examination of the data shows recreational athletes had somewhat worse LV function than inactive patients. Additionally, age of symptom onset and survival from sustained ventricular arrhythmia among recreational athletes appears to be midway between the competitive athletes and inactive patients, albeit not significantly different.

Recent studies from model systems have also implicated exercise in ARVD/C pathogenesis. Murine ARVD/C models with abnormal expression of two different desmosomal proteins (plakoglobin and plakophilin-2)54,55 have both shown evidence of earlier development of disease and worse structural abnormalities when exposed to endurance training. The molecular mechanism of this process remains unclear. Recent evidence suggests while reduction of desmosomal protein expression causes decreased cell–cell adhesion, expression of mutant protein results in cells with typical mechanical properties but abnormal signalling responses to stress.56

Cynthia A James holds grants sponsored by the National Society of Genetic Counselors and the Barth Syndrome Foundation. The Johns Hopkins ARVD/C Program is supported by the Dr Francis P Chiaramonte Private Foundation, the Leyla Erkan Family Fund for ARVD Research, the Dr Satish Rupal and Robin Shah ARVD Fund at Johns Hopkins, the Bogle Foundation, the Healing Hearts Foundation, the Campanella family, the Patrick J Harrison Family, the Peter French Memorial Foundation and the Wilmerding Endowments.