Screening and Diagnosis of Sleep-disordered Breathing

SDB can be reliably diagnosed with cardio-respiratory polygraphy, which records nasal flow, respiratory effort, saturation, pulse and position. The technology can be used in both in- and outpatient settings. Polygraphy has been shown to be a valid alternative to the gold standard polysomnography (PSG) for SDB screening and diagnosis.52–57 Attended PSG is currently the recommended option for assessing CSA in HF patients, but there is increasing evidence that polygraph

Implantable cardiac electronic devices also have the ability to screen for SDB by analysing changes in intrathoracic impedance, and this feature is being built in to newer models.61 Detection of SDB using implantable cardiac devices is not yet part of routine clinical practice, but there are devices currently available that are being used in clinical settings.

Questionnaires have not been useful in pre-screening patients with cardiovascular diseases including HF for SDB, because HF patients do not show the same symptoms and risk factors for SDB as patients without HF, and the screening questionnaires have only been validated for general OSA patients.23 In addition, the overlap of some HF and SDB symptoms make questionnaires less useful in this group of patients. Furthermore, mild SDB may not be associated with obvious symptoms but can still have a negative impact on prognosis.

Treating Sleep-disordered Breathing in Heart Failure

Current Options and Interfaces

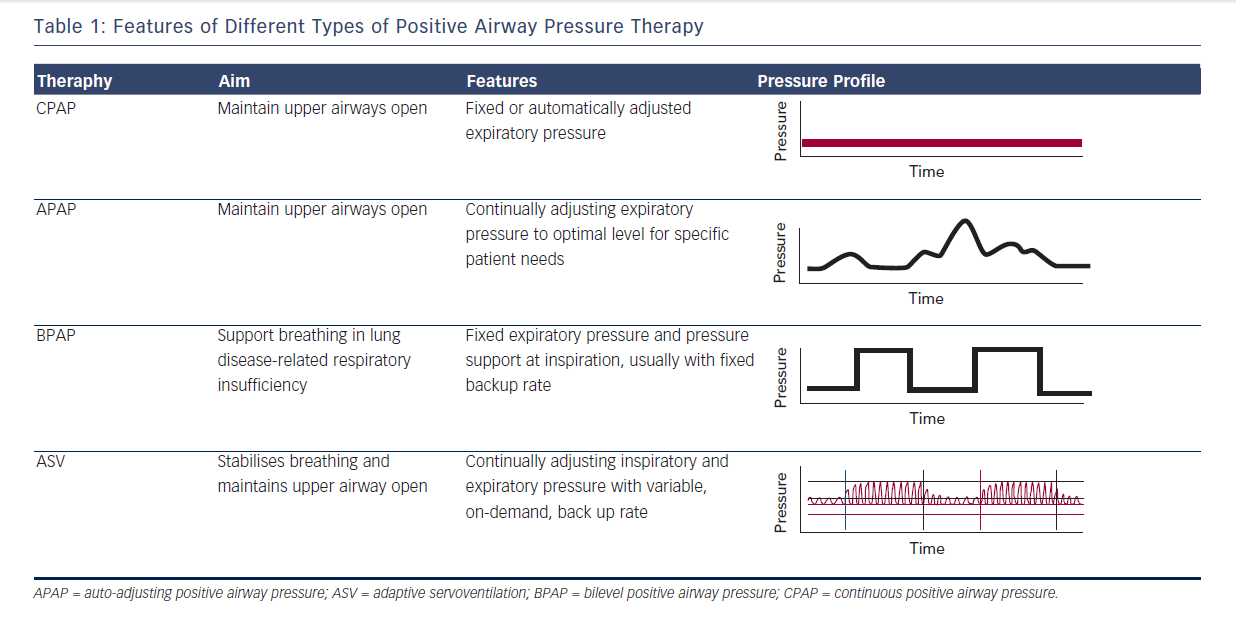

In addition to oxygen therapy, there are a number of positive airway pressure (PAP) treatment options available to clinicians managing SDB in patients with HF. These include continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), auto-adjusting positive airway pressure (APAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) and adaptive servoventilation (ASV) (see Table 1). Within these broad groups, there are a number of different devices utilising different algorithms to choose from. In addition to the selected PAP device, an important part of therapy is the choice of patient interface for delivery of treatment. These include nasal pillows, nasal mask and oronasal mask (sometimes known as full face mask); custom-made interfaces may be required in a small group of patients. The interface used for initiation of PAP therapy plays an important role in the acceptability of therapy and thus needs to be chosen carefully. For all therapies, the goal is to normalise breathing (AHI <5/h). An AHI of >5/h still meets criteria for diagnosis of SDB,62 and the aim should be to eliminate this negative prognostic marker, if possible. Data from the Sleep Heart Health Study showed that men aged 40–70 years with an AHI of <5/h.63

Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnoea CPAP maintains airway patency, enabling patients to breathe spontaneously and avoid intermittent hypoxia.64 Other beneficial cardiac effects in patients with HF include decreases in preload and afterload,65,66 a marked reduction in intrathoracic pressure swings64 and reduced sympathetic activity.67–69

CPAP treatment for OSA lowers BP, improves cardiac function69–71 as well as quality of life, can decrease the arrhythmic burden, and has been shown to improve survival in a cohort of HF patients, although this evidence does not come from randomised controlled clinical trials.72

There are potential treatment alternatives for specific OSA phenotypes, including weight loss, oral appliances, tonsillectomy and, most recently, implantable devices for upper airway stimulation. However, none of these have been tested in patients with concurrent HF.