Over the past 20 years, research and development in the field of oncology has produced significant changes and progress in cancer care. With the implementation of more aggressive cancer screening programmes, improvements in diagnostic testing and more effective treatment options, cancer death rates are gradually declining while cancer survivorship is steadily rising.1–3

Such statistics, however, have not been achieved without consequence, and are often offset by long-term adverse effects. While conventional chemotherapy has been known for decades to induce detrimental effects on the heart and peripheral vasculature, the use of novel agents are also increasingly being shown to have harmful off-target consequences to cardiac function. Thus, concurrent with advances in cancer therapies, so there has been a significant increase in cardiovascular side effects.4

One of the most common manifestations of cardiotoxicity associated with exposure to anticancer therapies is the development of left ventricular systolic dysfunction (LVSD) and overt heart failure (HF). As a result, the need for specialist cardiology input is becoming increasingly recognised as an important resource in the management of both long- term survivors and those undergoing active treatment. The aim of this paper is to review current opinions on the diagnosis, pathophysiology, management and prevention of chemotherapy-related cardiomyopathy, with specific focus on the commonest, and most studied culprits: the anthracyclines and monoclonal antibodies.

Definition of Chemotherapy-induced Cardiomyopathy

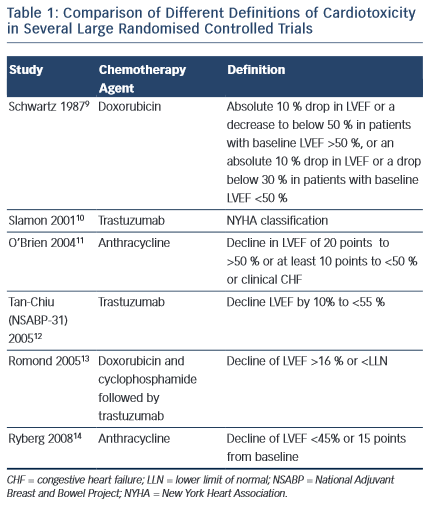

Despite the increasing recognition of chemotherapy-induced cardiomyopathy, consensus on international definitions in both clinical practice and trials remain lacking. Such definitions range from the development of HF symptoms, to the development of overt LV dysfunction and a reduction in ejection fraction (EF) on cardiac imaging (see Table 1). Indeed, the incidence of HF or LVSD in chemotherapy trials has been shown to range from 5 to 65 % depending on the criteria used.5,6 Moreover, it is widely accepted that chemotherapy- induced LVSD is often sub-clinical in the early stages, with overt changes in LVEF occurring after only a significant level of damage has occurred. Nevertheless, currently, a change in LVEF remains the basis for all definitions of cardiotoxicity issued by scientific societies in both Europe and the US.7,8

The research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Facility at Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.