Prevention and Management of SCD in Athletes

The steady trickle of SCD in athletes galvanises discussions relating to potential prevention measures in order to avert such tragedies. Proposed strategies include targeted evaluation of high-risk individuals, pre-participation cardiac evaluation of all athletes to identify quiescent conditions predisposing to exercise-related SCD, comprehensive evaluation of both the victim of SCD or SCA and most importantly of the family relatives who may harbor the same condition, and emergency response planning to ensure prompt resuscitation of cardiac arrests.

Primary Prevention Strategies

Targeted Evaluation of High-risk Individuals

Athletes with symptoms suggestive of cardiac disease or a family history of potentially inherited conditions or SCD should receive comprehensive evaluation. Of particular concern are new-onset exertional symptoms such as chest pain, shortness of breath, pre- syncope and syncope. This strategy in isolation is of limited value as the majority of victims of SCD are asymptomatic and SCD/SCA is commonly the first presentation.15,26

Pre-participation Cardiac Evaluation of Young Athletes

Pre-participation cardiac screening using the 12-lead ECG remains a controversial issue. Data from the Italian national screening programme in young athletes reported a 90 % reduction in SCD.8 In contrast, Israel’s introduction of mandatory PPS did not appear to alter the incidence of SCD in athletes.27 However, a possible explanation for the discrepancy is the difference in data collection methods between the two studies. The Israeli study collected mortality data from Israel’s two main newspapers and estimated the number of athletes in the population (denominator) for the earlier years of the study period.27 By comparison, the Italian study had well-defined population data and a robust national reporting system of SCD cases.8 Additional concerns centre on the inability of screening to identify a considerable proportion of conditions predisposing athletes to SCD, the false-positive ECGs, feasibility and cost-effectiveness.

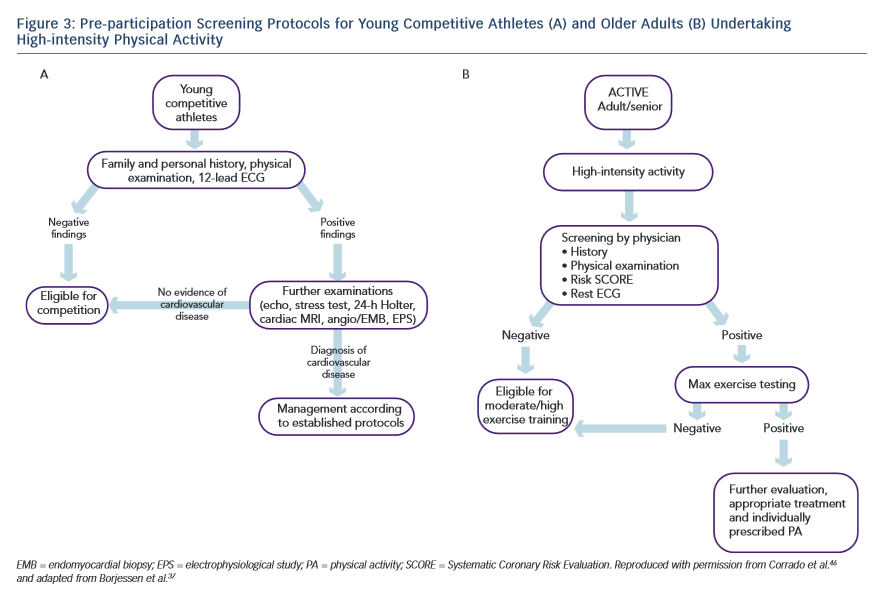

The Italian PPS programme is mandatory for all young competitive athletes aged 12–35 years. The first tier of evaluation involves history (including family history), physical examination and 12-lead ECG. If no abnormalities are detected, the athlete is eligible for competition. Those with positive findings suggestive of possible cardiac disease are investigated further based on local protocols and the condition suspected. If this second tier of targeted evaluation reveals no evidence of cardiovascular disease, the athlete is eligible for competition. Where a cardiovascular disease is diagnosed, the athlete is managed according to established protocols (see Figure 3A).28

The ECG is likely to raise suspicion of quiescent cardiac disease in the majority of individuals with cardiomyopathies and is the primary diagnostic tool for ion-channelopathies and ventricular pre-excitation. However, up to 10 % of patients with HCM,29 20 % with ARVC30 and 25 % with long-QT syndrome31 may exhibit a normal ECG. In addition, the resting ECG will not detect the vast majority of individuals with coronary artery anomalies.

The false-positive ECG rate using the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) criteria has been reported to be as high as 40 % in certain athletic cohorts, which raises concerns relating to the burden of unnecessary investigations or erroneous disqualification. Recent studies in large cohorts of young athletic individuals have resulted in refinement of the ECG criteria considered to denote an abnormal result,with a considerable improvement of the ECG specificity.32,33 Further research is necessary, particularly in athletes of non-Caucasian ethnicity, as the false positive ECG rate in athletes of African-Caribbean descent remains over 15 % and limited data exist on other ethnicities.34

Widespread adoption of PPS is also hindered by the lack of expertise and facilities. With the exception of Italy, where a mandatory, National screening programme has been in place since 1980, in most other countries screening of athletes is fragmented and dependent on the availability of local expertise and individual sporting organisation mandates. Finally, studies on the cost-effectiveness of PPS are fairly limited and most rely on theoretical projection models and arbitrary assumptions relating to the life years saved by identifying a potentially life-threatening condition. In most countries where the health service is already burdened by limited finances and resources, the implementation of a state-funded, national screening programme to identify silent cardiac diseases in young athletes seems unattainable.

There are, however, convincing arguments for alternative funding sources, with charitable organisations subsidising the screening of young athletes who wish to be screened for self-protection.35